Sergei Eisenstein and the Anthropology of Rhythm

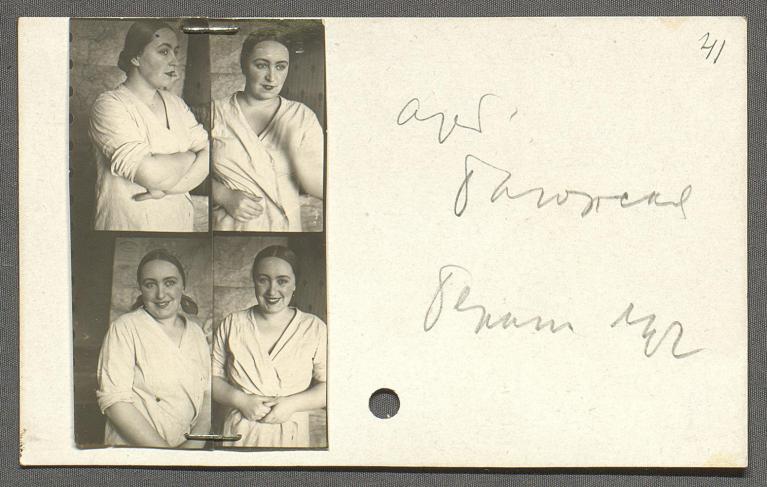

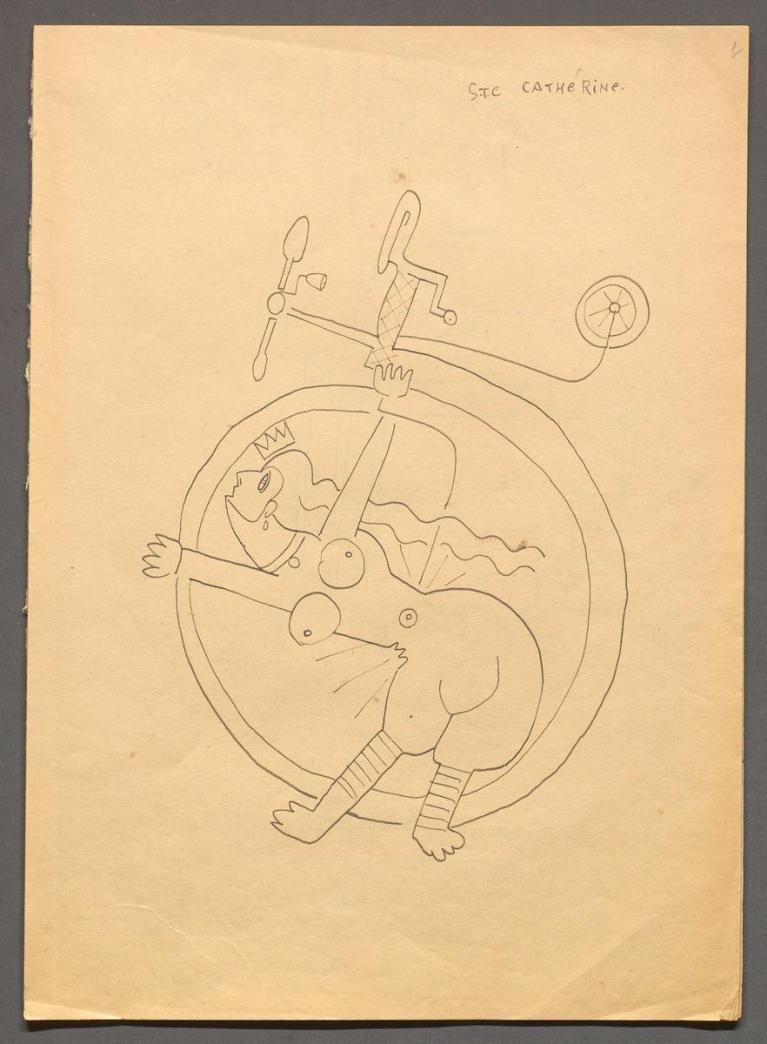

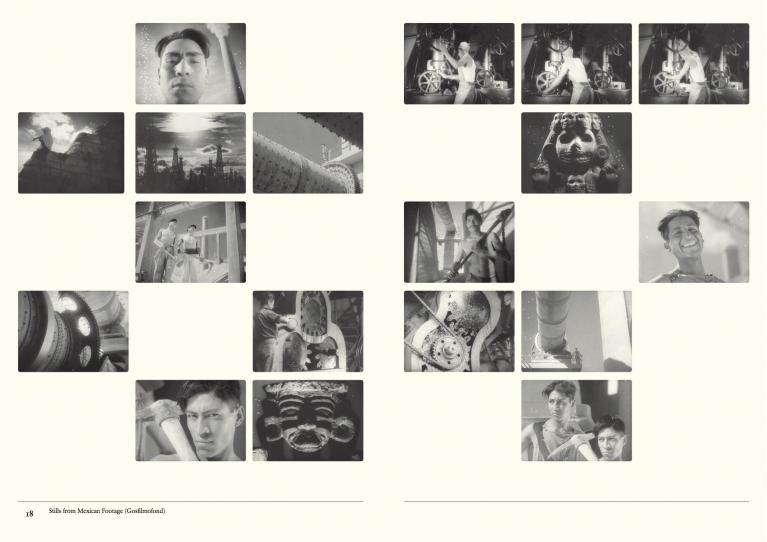

The exhibition Sergei Eisenstein: The Anthropology of Rhythm on September 19, 2017. Numerous documents from Eisenstein’s archives – The Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI) and The National Film Foundation of Russian Federation (Gosfilmofond) – will be exhibited for the first time, including notebooks, drawings, film footage and photographs. Curated by art and film historians Marie Rebecchi and Elena Vogman, in collaboration with the artist and typographer Till Gathmann, the exhibition will continue through January 19, 2018.

Here below is an excerpt from the introduction of the book Sergei Eisenstein: The Anthropology of Rhythm, published by NERO, Roma.

Out of poverty, poetry; out of suffering, song.” This is how the anthropologist and writer Anita Brenner describes the unfolding of a corrido, a Mexican ballad. Literally “event of the time,” the corrido is an anonymous poetic genre that musically voices the lament of the day. Whether recounting a political or personal event, a catastrophe or a bad dream, corridos lend rhythm to the sorrows of life, equally “for the servants, who wail them while washing dishes or putting babies to sleep, and for the muledrivers, who croon them to their caravans.” The necessity of rhythm has to do with its transformative power. It is a medium of change; it constitutes a transition from fear to joy, from ennui to awareness, from a simple movement to choreography or dance. For this reason, as Brenner points out, a collection of corridos is a “truer mirror of Mexican people, than any text yet written.” It transforms “a casual journalistic category” into a political event.

In its anthropological quality of organizing experience, rhythm is a vehicle of revolution. As Hannah Arendt once observed, it constitutes the etymological history of the word. Arendt pointed at the crucial tension of two opposing meanings of “revolution.” (N.d.R. On Revolution, 1963). Originating from the astronomical context where it defined a cyclical and regular motion of the stars, in modern times the word has come to define a unique historical upheaval of a given political order, enacted by man rather than by the cosmos or providence. What does the physical choreographic movement of turning have in common with the social and political change of a given situation? How does rhythm participate in this change?

This book proposes to explore the intersecting aesthetic, anthropological and political dimensions of three unfinished film projects by Sergei Eisenstein. The Soviet director (b. 1898, Riga — d. 1948, Moscow) is best known today as the paradigmatic author of revolutionary Soviet cinema. Yet there is another face to this Janus-like figure, many of whose unfinished film projects and extensive theoretical works remained unpublished and unknown during his lifetime — and to a certain extent until today. It is this as yet unacknowledged body of work which make up the subject matter of the present book. Focusing in particular on the anthropology of rhythm in Eisenstein’s Mexican project (Que viva Mexico!, 1931–1932), the book follows this thread to two other unfinished projects: the destroyed film Bezhin Meadow (1935–37) and Fergana Canal (1939), which came to a halt before filming even begun.

Rhythm and anthropology are closely connected. Organic and mechanical, regular and irregular rhythms are not merely formal, aesthetic or temporal aspects of experience. They can become instruments of anthropology. Pursuing both the aesthetic and the epistemic paths of this hypothesis, the book aims to reconstruct Eisenstein’s anthropological method through a series of archival materials: drawings, working journals and film footage. By placing Eisenstein’s method in a constellation between the heterodox surrealist aesthetics of the French journal Documents on the one side, and the anthropological culture of

post-revolutionary Mexico on the other, it explores the paradigmatic modern experience of looking alterity in the face.

By focusing on the representation of people, in particular the intense and astonishing variety of ways in which Eisenstein filmed human faces, the presented materials illuminate hitherto

unknown documentary and ethnographic facets of Eisenstein’s work. In his images from Mexico and his later anthropologically-oriented film projects in Ukraine and Uzbekistan, Eisenstein brings the two meanings of “revolution,” as evoked by Arendt, into play. Here we perceive the emerging relations of history poised between repetition and irruption, return and revolt , between a single destiny — a body or a gesture — and the social

and political narrative that constitutes its background. Each of these film projects invents a new and unique cinematographic approach, yet they all share a common archaeological model of history and an anthropological construction of the gaze.

By turning the filmed faces to profile, moving them away from the focus of the camera, revolving them in an ecstatic dance, or dissolving their visibility behind a mask, human faces are made to defy the prevalent physiognomic, criminal or racial paradigm. These images unfold a concrete spectrum of possible metamorphoses exceeding any fixed identification. They critically deface the static notion of the human figure, turning it into a rhythmic multiplicity of itself, dismembering and decentering its unity. This intense animalistic or even cannibalistic understanding of mimesis originated in an anthropological opening of a history of culture incorporating the extremes of its social and religious manifestations. In Eisenstein’s images and working diaries from Mexico — selections from which have been translated for this book — rhythm becomes a powerful mimetic instrument of alteration.

Elements towards a “Lay Anthropology”

[We want to thank philosopher Pawel Moscicki for having inspired this title. A research project on “lay anthropology” encompasses works based on the experience of “lay” ethnographic research].

What is the epistemic risk of this experience, and how does it relate to other forms of knowledge about cultural formations? An interesting parallel comes from the field of psychoanalysis. In his text on “Lay Analysis,” Sigmund Freud raises the question of

the authority of the analyst vis-à-vis his patient and, as a consequence, of the epistemic ground of psychoanalysis as a “science.” This “practical” question leads Freud to distinguish the conditions of psychoanalysis from those of medical treatment.

“For we do not consider it at all desirable for psychoanalysis to be swallowed up by medicine and to find its last resting-place in a text-book of psychiatry under the heading ‘Methods of

Treatment’, alongside of procedures such as hypnotic suggestion, autosuggestion, and persuasion … As a ‘depth-psychology’, a theory of the mental unconscious, it can become indispensable to all the sciences which are concerned with the evolution of human culture and its major institutions such as art, religion and the social order. It has already, in my

opinion, afforded these sciences considerable help in solving their problems. But these are only small contributions compared with what might be achieved if historians of culture,

psychologists of religion, philologists and so on would agree themselves to handle the new instrument of research which is at their service. The use of analysis for the treatment of

the neuroses is only one of its applications; the future will perhaps show that it is not the most important one.”

The theory of the “mental unconscious” cannot be reduced to the subject of an individual psyche because it relates to the culture as a whole. At the same time, the analytical situation is not only a matter of the relation between analyst and patient. The unconscious involves a more complex temporality: a process wherein individual and social orders, singular and collective experiences, are intimately entangled.

In defending lay analysis, Freud addressed the irreducible potential of the unconscious; precisely for this reason, the analyst would never be legitimized or qualified by psychoanalysis on its own. Opening this epistemic breach, Freud focuses on the process of transference, where the “requirements of the analytic technique reach their maximum.” According to Freud, the analytical process itself is based on the motoric and rhythmic

“reproduction” of the suppressed experience rather than on memory. The analyst’s own engagement with the potential for transference between himself and his patient involves facing up to this unconscious flow.

Eisenstein’s experiences in Mexico could be described as “lay anthropology” based on the same epistemic ground evoked by Freud: the practice of a non-professional, vernacular discourse, not secured by any institutional authority or disciplinary ethnographic knowledge.

[…]

Eisenstein’s anthropological gaze does not only realize a step beyond disciplinary boundaries. It was a more audacious movement beyond his own intellectual, political and cultural context,

exposing himself to his “epistemic object” with an emphatic closeness verging of identification. This physical contact, including an immanent process of transference and counter-transference, distinctly affected the modes and methods of this anthropology. “Cannibalism,” we read in Eisenstein’s Mexican diary, “needs to be included in the totality of the imitation (identification) practices.” Whereas the Aristotelian concept of mimesis stresses the distinctness of the imitation from its model, what Eisenstein called the “cannibalistic” mode of mimesis eliminates all distance between them: it subsumes difference through consumption and transformation. Following this logic, Eisenstein asserts that “gentle stroking is a punch in slow-motion (sadism is only a stage in the tempo and intensity of stroking … devouring remains in love only in the form of a bite and a kiss.”

Such a rhythmic pulsation of polarities — similar to Freud’s essay on the “antithetical meaning of the primal words” (Gegensinn der Urworte) or Warburg’s concept of “energetic inversions” in the extreme expressions of pathos — can be seen as an anthropological spectrum of shifts in the process of transference.

Although Eisenstein was never able to edit his Mexican footage, we can discern through his aesthetic choices an immanent montage of the planned film. This is the case with the highly prevalent gesture of turning one’s head : we see masked and unmasked faces, Christian and pagan masked dances, contemporary faces juxtaposed with monumental ruins of Aztec and Maya cultures. Here, the attempt to find a heuristic pattern — a melody — in the material gave rise to a veritable anthropology of rhythm.

[…]

Beyond a mere metaphor for the reversal of power relations, the turning body provides Eisenstein with a formal tool for the shifting of perspective: in the process of turning, the figure connects with its background in a mutual plastic transformation. In this visual quicksand, the relation between the foreground and the background is itself put into motion. It is neither en face nor in profile, but rather in the face’s metamorphic mobilization that Eisenstein locates the political and social potential of what is given to the eye. While developing his politically-motivated work with amateur actors in Mexico, Eisenstein expanded the practice of tipazh [the Russian word “tipazh,” English “type,” is a concept for typical appearance, representative of a social class. This is how Eisenstein and other Soviet cinema pioneers referred to a non-professional actor as opposed to a professional one. The political formula of tipazh quoted by Eisenstein, was a “social biological hieroglyph.”] to an experimental visual anthropology. He turns the Mexican faces into abstract landscapes, paradoxically revealing the cruel history of the country and its people. Turning the faces to profile and back again, he morphologically discovers the relations between different layers of history: the connections between modern Mexico and the ruins of archaic Aztec and Maya cultures; the syncretic intersection of pagan and Christian rituals and traditions.

Marie Rebecchi / Elena Vogman (in collaboration with Till Gathmann),

Sergei Eisenstein and the Anthropology of Rhythm.

128 pp., 340 images, partly in colour.

Published by Nero, Rome, 2017