Speciale

Contemporary African Art: A question of label?

When I was asked to work with a new contemporary art gallery focusing specifically on African artists, my first reaction was, of course, one of joy and excitement, not only because this was the kind of job I had always longed for, but also because the word “African,” associated with contemporary art, triggered a number of ideas, thoughts and impressions on which I had been reflectingfor a while. First of all, why do we talk about“African” art? This is not a merely geographical designation, as this label is also used to indicate works by artists of African descent born and/or based in other countries, as a consequence of the so-called “diaspora.” Besides, North African art is usually regarded as a category of its own, due to its “Arab” and “Islamic” influences. Therefore, “African” art is neither a geographical label nor a category in itself, as there are no stylistic, thematic or technical features that can univocally be attributed to it.

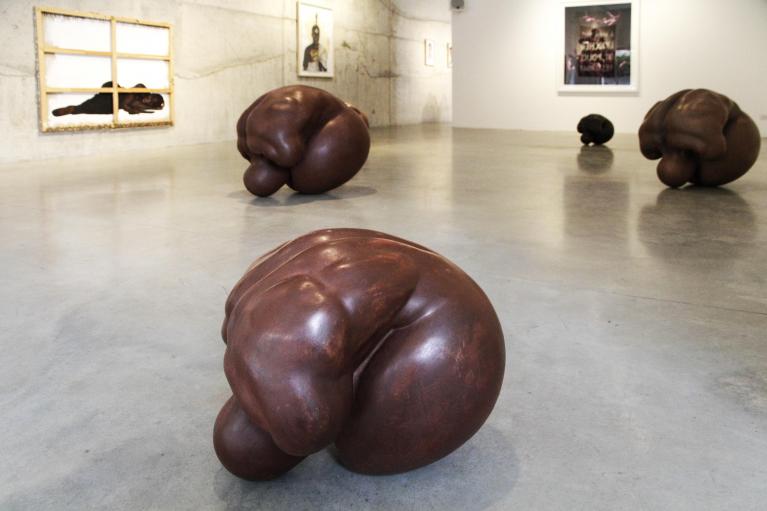

C-Gallery, Room 1, Maimouna Guerresi – Kimathi Donkor - Mary Sibande - Robert Pruitt , courtesy of C-Gallery and the artists.

Yet, most of the 2017 spring cultural events in Paris were about “contemporary African art” –from Art Paris Art Fair, which had Africa as a guest of honor,to a number of exhibitions and conferences spread across the city. The 2016 Armory Show in New York also put the spotlight on Africa, and so did many other institutions and exhibitions around the world. Based on this, one would assume that “contemporary African art” must be something quite specific, but how can we define such specificity? When describing Africa, the West has never been able to get rid of its long-standing imperial gaze. The Magiciens de la Terre exhibition, for example, had the merit of bringing a number of artists from all over the world to the attention of large audiences, but it was not able to go beyond the mere reproduction of power relations between French culture and minorities. Thus, it failed to give equal dignity to the exhibited works and artists, perhaps because the audience was not ready for it; and this inevitably gave way to exoticism, with foreign cultures presented as variations from the norm, which was obviously identified with Western culture. Things do not seem to have changed much since then.While this current focus on contemporary African art has certainly given visibility to artists affected by a center-periphery hierarchical perspective, this glorification of minority as such is indeed counter-productive.

C-Gallery, Room 1, Maimouna Guerresi - Joel Mpah Dooh - Coby Kennedy , courtesy of C-Gallery and the artists.

By labeling contemporary art as “African,” we mark it as different from non-African contemporary art and fall into aninclusion/exclusion trap, creating a perception of difference where there was none to begin with. Suffice it to say that most contemporary African works of art cost less than their non-African counterparts, although being created by equally talented artists. So why is this distinction still made? I have been asking myself this question for months; the answer would probably open up a number of other issues that would be difficult for me to sort out. I wonder if I’m not too permeated with my own Western culture to see that an African specificity does exist. What if my tools are actually too limited to approach these matters? What if the otherness of “contemporary African art” is actually a form of resistance to the Western art system and its delirious market, a form of self-defense and self-differentiation that we create to make clear that the Western system is not the only one, but there is also a parallel and different African system with which it is possible to interact without merging. I have difficulty believing that this is the case; or rather, I don’t think this can be a winning and lasting approach in a globalized world where market embraces everything in order to survive.

C-Gallery.

As far as I can see, another danger exists: the danger of turning this“African art” label into a market trend, into a speculative bubble that pushes up sales as long as it is necessary, until a new trend comes out and replaces it. If this were the case, then “contemporary African art” would only be a moment in history, rather than history itself. In the end, I ask myself how I can contribute, as a curator and gallery manager, to avoiding these traps, and encourage others to follow suit. This is my challenge, but it is also the challenge of our present time. Perhaps, we need a great cultural revolution that will eventually make all these issues pointless. What I know is that history will certainly find its way, and I hope this time it will be a history written by many, by all.

Photos by Raffaelle Bellezza.

Traduzione di Laura Giacalone.

With the support of