Speciale

No One Told Me: A Gap

Looking back over the 20th century, it seems that the predominant story concerning the continent of Africa is an imagined one. From explorers to missionaries, from colonizers to reporters, the record of Africa (and by record, I mean the way that Western minds are accustomed to charting history: books, journals, newspapers, archives, etc.) was written, photographed, and performed by outsiders. Bofa da Cara (Pere Ortín & Nástio Mosquito) captured this historic monopoly on defining the “Dark Continent” in their video montage, My African Mind (2010).

Bofa Da Cara, My African Mind, 2010, screenshot from the video, 6’11’’. Courtesy Bofa Da Cara

But today we are enlightened, right? We—whoever you imagine when I say ‘we’—are trained in cultural sensitivity and inclusivity. We are a post-Magiciens de la terre world! In reality, there are other layers of complexity to consider in measuring the advancement of Africa’s artists.

While art circles have made strides in representing and exhibiting artists of African descent—from an increasing number of solo shows (Ibrahim El-Salahi at Tate Modern, El Hadji Sy at Weltkulturen Museum, or Zanele Muholi at The Brooklyn Museum), to Africa’s prolific presence at biennials worldwide (including the landmark participation in Okwui Enwezor’s All the World’s Futures for the 2015 Venice Biennale)—there remains a group of people for whom Africa is still an imaginary place.

Installation of Zanele Muholi's Isibonelo/Evidence at The Brooklyn Museum exhibit, 2015. Ph. Joseph Underwood

Speaking as an American, I see an uneducated majority who are insensitive to not only the discussions being generated by contemporary artists/activists, but also to matters that concern the Global South at large. For those citizens who do not ask, who do not search, Africa represents a lingering vestige of poverty, disease, and violence. Despite technological advances and the terabytes of available information, today’s average Instagrammer or Tweeter knows no more about contemporary Africa than a citizen of 19th century Europe. Their perceptions are shaped by the cloying stories of NGOs who exist to “raise awareness” or by the villagers from Broadway’s Book of Mormon or by whatever viral video campaign warns them about Joseph Kony. Though some artists speak to these topics—like Sam Hopkins’ series on real or fictitious NGO logos in Kenya—our biennials, articles, and conferences rarely meet the general public’s purview and, consequently, do not help to realign these misperceptions.

Sam Hopkins, Logos of Non-Profit Organisations Working in Kenya (Some of Which Are Imaginary), 2010 and ongoing. Ph. Sam Hopkins

In the United States education system, Africa is a black hole. From politics to art and everything in between, students interact with the canon of Western forefathers, learning of French monarchs, Dutch reformers, and American patriots. They read about World War II, learn Greek astronomy, and read British literature. The only introduction to Africa comes when learning about the exotic animals or through a summary lesson in geography that includes a few pictures of mud huts that stand in for the whole continent. So what fills in the gaps? Though there are more than one billion people on the African continent, the average Western mind can only conjure a few types—for these images, I send you once again to the caricatured Africans in Ortín & Mosquito’s video: warlord, peasant woman, starving child, ancient warrior, nude native.

This story is my own. As I contemplate the question of “Why Africa?” I am first confronted with the question “Why me?” A descendant of Kentucky on one side and China on the other, I received a standard American education. I attended an excellent liberal arts university, studying art history and French… yet the majority of my exposure to Africa was through watching Animal Planet. In the States, there is no integration of Africa’s history or culture without intentionality. If educators—at all levels—do not actively feature productions from the global South, the paradigm doesn’t shift.

Installation of Toguo/Cissé at Galerie Le Manège, 2010 Dak'Art Biennale, Senegal. Ph. Joseph Underwood

My first visit to Dakar challenged a lifetime of misinformation I had absorbed. To any observer or critical thinker, it quickly becomes obvious that Senegal does not stand in for all of Africa—and neither does Dakar stand in for all of Senegal, nor one arrondissement for another. Homogenization quickly breaks down into idiosyncrasies and particularities. There is no single national/regional type of people, just as there is not a monolinear style of art.

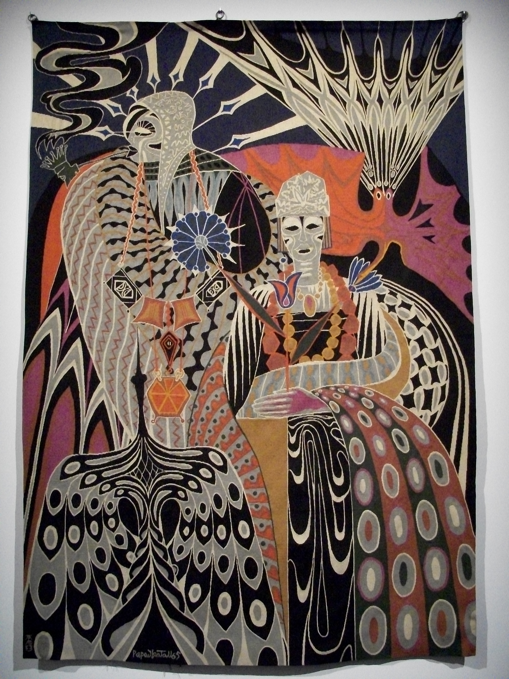

I make no claims to be enlightened. I didn’t undergo some kind of primeval return and discover a forgotten part of my self. I only began to hear the voices that are not included in the canon’s deluge of Occident-centric information. The products from Africa have always been vibrant and in dialogue with international partners. It is due to systemic unbalance, though, that history has suppressed these contributions. With guidance, any individual—much like myself—can learn that the seemingly generic tribal dance and “primitive” native art are, in fact, the complex goli masquerade of the Baule and the ancestral spirit Nommo figures of the Dogon. We can learn of Ezrom Legae’s powerful abstracted sculpture during Apartheid, or of Papa Ibra Tall and Iba N’Diaye’s contributions to African Modernism and the École de Dakar, or of Chéri Samba’s groundbreaking presence at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1989. We would no longer be surprised at the presence of new media—digital, video, sound—in the oeuvre of African artists.

Papa Ibra Tall, Royal Couple, 1965, acrylic on board. Ph. Joseph Underwood

This, then, is my small corner. Having learned in the dark for the majority of my education, I gleefully share this new knowledge (the history is not new—just new to me) with my own students. Whether it’s the single-mom math major, the student who completed two tours in Afghanistan, or the exchange student from South Korea—each comes into the lecture hall with his or her individual background and unique learning experiences. The common denominator? The same common denominator that underlies my classes, my colleagues, my “cultured” friends, my course’s textbook, and my Facebook newsfeed: a few antiquated and misguided stereotypes of Africa that define their knowledge of an entire continent. And so I teach… the courts of Benin and their mastery of bronze, the Colonial Exposition of 1931 and the displacement of West Africans to Paris, or the literal reshaping of history books in Wim Botha’s strained figures.

This is my response to “Why Africa?” It is not a defense of Africa’s significance or why it should matter in the world. Africa doesn’t need to be defended. It’s our ignorance that needs a defense. My response is addressing a gap. It is because I should have already known. It’s because my children and their children should not receive a modern education and then have to relearn the parts about Africa. It is because the students in today’s universities should not graduate and go on to affect policy, create businesses, or define entertainment if their knowledge of these rich African heritages and contemporary contributions are limited to Cecil the lion and Ebola.

With the support of