Speciale

Sue Williamson, Chronicler of Memory*

It was 2008, and the Palazzo delle Papesse in Siena was hosting a collective exhibition of young artists from South Africa. Among them, a still-unknown Zanele Muholi with her Miss D’vine series and other works focused on the South African LGBT community. My journalistic interest in African contemporary art (whatever this expression means to say) began with those images, which represented the starting point for an investigation into South Africa’s “corrective rapes,” the hateful and recurring practice of abusing homosexual women to bring them back “on the right road.” Muholi’s shots concretely show how much testimonial strength and denunciation art can hold. They offered a key to understanding, a way to access a country in transformation. They were the meeting point between poetry and chronicle, between expression of self and social commitment. Something very close to my concept of writing.

Muholi’s presence at the Papesse was strongly called for by Sue Williamson, a South African artist who was among the curators of the exhibition. For this reason, I felt I owed her a debt ever since. When I had the opportunity to interview her, thanks to Skira, publisher of the monographic book Sue Williamson. Life and Work, I couldn’t believe it.

Defining Williamson as an artist is correct, but also simplistic. Because this gentle and kind woman wanted to be—and managed to be—many other things: a narrator, an activist, a promoter of creativity, culture and commitment, a witness and chronicler of memory, ready to state her position, while never losing sight of the complexity of a situation.

Her parents were English, and moved to Johannesburg in 1948 when Sue was seven years old. Growing up under apartheid, many things bothered her (beginning with, for example, the Afrikaans language that she could never master) but she did not worry too much about anything. She began working as a journalist and at age 21 married. Shortly thereafter she moved with her husband to New York, where she discovered a passion for the visual arts. After the birth of her first child, they decided to return to South Africa, to live a more peaceful life. But in 1976 came Soweto’s uprising, Hector Pieterson’s death along with dozens of students, awaking Sue from her “soul’s lethargy.” She began to look around, to ask questions, to find the whole situation unbearable.

A few months later, at a public gathering, she listened to the writer Sindiwe Magona (if you have not read anything of hers, I strongly recommend that you do) exhorting South African women—black, white, and mixed—to join in a non-racial movement. She found herself “overwhelmed” by the idea and realized that she had never really had any awareness, until that moment, of what surrounded her. She became one of the founders of the Women’s Movement for Peace. She went to see what was happening in the so-called squatter camps repeatedly dismantled by the police—observing, drawing, collecting material, redesigning it into artistic projects of great impact.

It was in this way that series such as The Modderdam Postcards (1978) and the installation Last Supper (1981) were born. In the first, she started with her sketches from her visits to Modderdam during police raids, creating postcards on which she posted a series of messages from a hypothetical official of the Bantu Affairs Administration Board (the department responsible for monitoring the effectiveness of segregation) that could have been sent to a colleague or a friend. The second is a composition of furnishings and various items collected during the District Six demolitions and is exhibited within a virtually white space at the Gowlett Gallery in Cape Town. They are works that tell not only of the brutality of apartheid, but link the very worlds that the regime wanted to keep separate.

In 1989, a crucial year for South Africa and the world, she published Resistance Art in South Africa. “This book is about how my generation’s artists responded to the truths that the events of 1976 had finally made clear,” she writes in the introduction. This is a book that is vital for understanding the South African creative scene of those years, the transition from an essentially elitist and non-socially engaged practice to one that confronts the society and desires to transform it through multiple tools and languages.

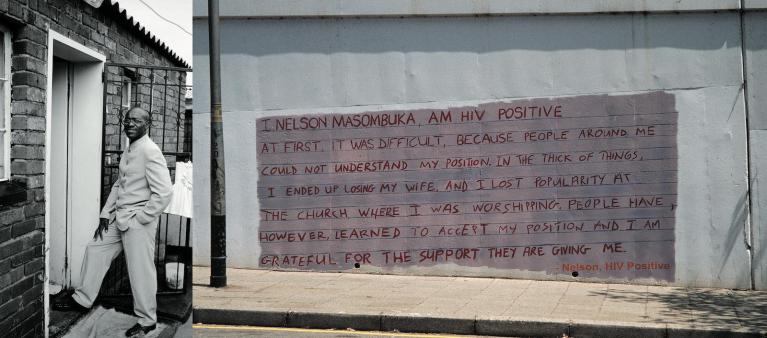

The intertwining of visual art, narration, dedication and testimony emerges through Williamson’s entire production. With the end of apartheid, it does not lessen but evolves by touching other issues, using new media (video, digital graphics) and, particularly in recent years spanning the boundaries of space and time. This brings to mind the series From the inside (2003), which tells what it means not to die but live with HIV; the video installation There’s something I must tell you (2013), which shows emblematic feminine figures of the apartheid struggle speaking with their grandchildren, who are dealing with completely different problems; and the traveling workshop Other Voices, Other Cities, which has touched cities on all continents and is still ongoing. In this workshop, participants are asked to find a phrase, a message that expresses the essential character of the place where they live, and turn it into a photographic representation.

Incidentally, on the cover of Life and Work and also in the Notebook that Williamson made for the At Work project from lettera 27, there are some of the pictures of the Johannesburg project.

The constant element of Williamson’s path is social commitment. Artist and Nigerian art historian, Chika Okeke-Agulu, points this out in his introduction to Life and Work: in many African cultures it is also semantically impossible to separate the concept of ethics from aesthetics, creativity from the commitment to the community. Art that is not social is inconceivable. Williamson embodies this impossibility and, in a sense, goes further because all her works, without exception, always have a participatory nature. There have been some who have challenged her for this, such as the South African critic Thembinkosi Goniwe, who claimed a few years ago that Williamson was working too much “for others” without ever exposing herself. In fact, the choice to favor the stories of “others” and to work “with others,” to focus on specific subjects (women, victims, migrants) and themes (corruption, abuses, identity) are revealing steps which say a great deal about the person who makes them. But Williamson, on that occasion, cut the discussion short, saying that she always felt first and foremost a reporter.

What is the link between your art and journalism?

Curiosity, the need to understand. I know that I am very curious: in particular, about the stories of people, and what young and old people think about South Africa. I am interested in understanding how young people see the country today, if the crimes of apartheid can be forgotten, if the conditions are there for finally addressing gender issues…My research starts with these themes. For example, at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris (Ed: during the collective exhibition Être Là. Afrique du Sud, une scène contemporaine), I brought It’s a pleasure to meet you, a two-channel video in which two 20-year-old strangers—with nothing in common but having been raised fatherless due to apartheid—have a conversation. The woman went to the jail to meet her father’s assassins and says: “I needed to know the details. Now that I know what happened, I can forgive them.” But the young man is in a completely different situation. Thus begins a discussion of forgiveness, of the conditions that make that possible, and of the effectiveness of the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation. I gather testimonies, and I feel the need to share the relevant things I come to know, just as a journalist would do. Even if later I do not write the article.

You immediately focused on the black population of South Africa. The series A Few South Africans (1983-87) comes to mind which, during very difficult years, gave a public face to the women who fought against apartheid. Was it complicated for you, a white woman working with blacks?

Less than you could imagine. To portray, recount, testify—these are always very complex operations. Subjects may not feel fully represented. I have always tried to be honest with people, explaining to them what I am doing and why, engaging them and inviting them to actively participate, highlighting the political goals. There have also been criticisms, I agree, but in general I have been understood. And in many cases I’ve created strong, real, lasting personal relationships.

What changed with the end of apartheid?

Until 1994, I was mainly concerned with emphasizing the role of women in the struggle for liberation. Obviously with the first democratic elections, a new era began. South Africa has one of the most advanced constitutions in the world, banning all types of discrimination. But the reality is different. There are many open issues: the economic power that remains in the hands of whites, for example. Then there’s AIDS, corruption, gender violence, corrective rapes that women have come to know thanks to Muholi, racism against immigrants from other African countries.

Let’s talk about this. You devoted your series Better Lives in 2003 to this theme.

The growing economy had already been attracting many people from Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique. But with the end of apartheid, the flow intensified. The locals, who had been waiting for years to have homes, schools, electricity, were very resentful. They forgot the past, the stories of migrants are the same throughout the world. They come to a new country with nothing, but are ready to work hard, to accept brutal conditions, and this triggers a type of competition among the poor. In Cape Town, wherever you want to park, you find “guardians” ready to protect your car for a few Rands. If you talk to them, you discover they’re university graduates and have the best intentions. But the indigenous people do not see them this way… This is a problem that, due to the country’s past, has become particularly paradoxical, but in reality has a global reach, referring to the issue of identity, freedom of movement, and environmental fragility.

From an artistic viewpoint, South Africa is often considered “not Africa.” What do you think?

South Africa boasts galleries, museums and infrastructures in the standards of Europe or America. That is why some would like to consider it a Western branch. But the truth, historical and geographical, is that this country is in Africa. The problem is the persistence of a neocolonial attitude towards Africa. Western curators too often want “African looking” works, referring to wooden masks, drums, and an exotic crystallized repertoire. They insist that anything that differs from these stereotypes is non-African. But in South Africa (and not only there) a lot of things are different: it is a reality. Instead of changing the view and admitting the complexity and plurality of Africa, however, there are those who suggest that South Africa belongs elsewhere. From this distorted view comes a great difficulty for all African artists in general, who neither want to nor can separate themselves from their culture and history, but at the same time be locked in a ghetto. They are facing a choice (stay or leave) that endangers their identity and creative freedom.

To stay or leave: The dilemma of the artists of the “island” of Africa was the title, incidentally, of one of Williamson’s papers presented at the 2008 Papesse exhibition. It focused precisely on the difficulty of creating art in Africa, showing the concrete and theoretical limits of the expression “African contemporary art.” Also in this, Williamson represents an emblematic figure. Because beyond the theoretical contributions to this debate, it is her work and biography that reveal the ambiguity of a label that is in some ways still needed (to facilitate communication with laymen, to better define subject boundaries, to organize volumes in a library, etc.), but is now, as never before, dramatically inadequate.

* Interview held on June 5, 2017, at the Bocca historic library of Milan. Photos: Dante Farricella. Translation by Laura Giacalone