Speciale

Respectable Memories / Postcards from South Africa

A Short History of South African Photography, by Rory Bester, Thato Mogotsi and Rita Potenza, is an exhibition hosted by Fotografia Europea XII at the Cloisters of St. Peter, Reggio Emilia, to celebrate the 40thanniversary of the agreement (June 26, 1977) between Reggio Emilia and the African National Congress, and the centenary of the birth of Oliver Tambo (1917-1993), leader of the anti-apartheid movement and the ANC.

Chronologically ordered, it is a selection of images that traces the history of South Africa from the dominion of the British Empire to present day. The shots come from archival collections (Die Erfenisstigting Archives, UWC Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archive, BAHA, Transnet, Times Media, Independent Media Archive), museums (Museum Africa, McGregor Museum, Smithsonian Institution), and artists. It is notable how the authorship of individual photographers gains more and more importance as the show moves forward, progressing closer to the present day. This also marks a shift from a photograph that is historical documentation to one that is historical metaphor.

It is a surprise to me that it is still preferable to devote space to the reconstruction of the memory of a former British colony, rather than to the Italian colonial history, especially at a time in which the racist connotations of the word ‘integration’ increase in volume and quantity. An interesting ‘oversight’ is on the ground floor of the cloisters where, at the entrance of the Berengo Gardin exhibition, a large picture of the artist's studio also features African masks from his collection. I call that an ‘oversight’ because, while I do not blame the curators of Berengo Gardin's exhibition, I think it is particularly symptomatic of the slow evolution of the decolonization mindset within our geographic boundaries, as proved by the (avant-garde?) spoils of past Cannibal Tours.

The exhibition A Short History of South African Photography is an example of how it is possible, working with archives, to not only present but absolutely construct and select a story and a memory that are not necessarily collective. In fact, as can be expected, almost every shot up to the 2000s was made by white photographers. Indeed the show's viewers, myself included, are all white (which is quite common in Italy).

Jodie Bieber, The Silence of the Ranto Twins, 1995, Courtesy the Artist.

Opening the show is a shot by Abe Goldstein about a miners' dance in Johannesburg in 1920. Many visitors to the South African mines in the 1920s were invited to watch these traditional dances performed by African miners. Photos of these performances for white visitors were common in that period and would appear on postcards, and business and tourist brochures. In the Goldstein shot, it is not clear whether it is a staging or spontaneous act. In this way, a photograph is capable of censoring the memory itself: the colonial gaze is inherent in everything that is not seen and which remains hidden.

Photography is not only a form of testimony, but is also, above all, a form of interpretation of history, as can be seen from the comparison of two images dated 1928: in the first, the South African women's national swim team consists of white women in either a swimsuit or uniform; in the second, The Waterbearers of the Venda Tribe of Sibasa are portrayed by Irish photographer Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin. The connection of the two photographs reveals an ethnocentric prejudice: in seeking the nakedness of primitive man, Duggan-Croninimmortalizes it from the "objective" point of view of the European ethnographer.

Coming from Museum Africa is a photograph taken in Pretoria in 1938, depicting A Parish Priest with Two White Men Dressed as Zulu Warriors During the Celebrations of the Great Trek Anniversary, the "great migration" of the Boer colonists (in Dutch, "farmers") who, in rebellion against the policies of the British rule established in 1835, left Cape Colony and headed north, where they founded some republican communities beyond the Orange River, across into Natal and beyond the Vaal River. This carnivalesque image reminds us that, when slavery began in 1658, the first schools were run by confessional churches, and the fact that one of the consequences of the Great Trek was the establishment of the apartheid regime. Thus, a disconnection can be seen between the documentation and representation of apartheid: by focusing on minor details, in this case almost humorous, a vast part of reality is left outside the visual field of the images.

In 1949, the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, designed by Gerard Moerdyk (1890-1958), a great admirer of Mussolini, was inaugurated. To represent the event, celebrated in the city’s amphitheater, the exhibition curators chose a shot from the Die Erfenisstigting archive, where the separation between a white and a black crowd is highlighted. The inaugural ceremony held on December 16, 1949, commemorates the triumph of Voortrekkers over the Zulu inthe Battle of Blood River in 1838. It is an attempt at reconciliation between British and Afrikaner settlers.

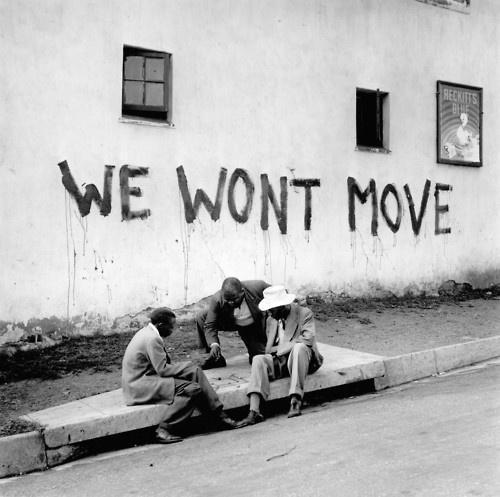

In a photo on the opposite wall it is possible to see three well-dressed black men playing a sort of tic-tac-toe game on a sidewalk. Behind them, on the wall of a building, are the words "We won’t move." This photo, titled Waiting to Commence Forced Removals, was shot at Sophiatown around February 9, 1955, when D.F. Malan sent 2,000 police armed with guns and rifles to destroy Sophiatown, and remove and relocate its 65,000 inhabitants to Meadowlands. The National Party set up a residential-reserve enclosed compound with homes devoid of toilet, water and electricity. What is emerging also here is therosy and glossy portrayal of an episode of mass racism. Instead of the dead and the deportees, the photographer decided to capture three well-dressed men playing. In fact, even in fascist colonial photographs, the "indigenous" rarely worked.

Jürgen Schadeberg, We won't move, Sophiatown , 1955

However, I find it problematic that an image like this is "left as is" without accompanying explanations that mention the Natives Resettlement Act of 1954 by the National Party, or that suggest the disguised violence in a propaganda image. One may think the fault lies with the ignorance of those who cannot decode an image because they do not know the history of South Africa. But what if this happens within an exhibition that aims to illustrate a Short History of South Africa? With what impression can a visitor leave such exhibition if complete contextual information is not provided? Probably with the same impressions that come from a honeymoon safari or hunting trip between whites to South Africa.

Eli Weinberg is the photographer of We Stand by Our Leaders, portraying a crowd near Drill Hall, December 19, 1956, on the opening day of the Treason Trial of Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders. Roads outside the courtyard are crowded with thousands of demonstrators. In the shot, a row of people of color, sympathetic to the accused, are seen in a polite and dignified manner. Men and women carry signs, "We Stand by Our Leaders"; among them, a smiling white baby in shorts and with a wristwatch stands out. He is the son of the photographer.

Eli Weinberg, We stanbd by our leaders, 1956, courtesy Times Media Collection.

Photographs like this, taken in public, show a form of complicity or obligation, mediated by the relationship between the photo’s subject and the white photographer: the apartheid system — with its immense resources of physical intimidation, bureaucratic control, and psychological coercion — causes the opposition, under the control of police and soldiers, to remain "in their place." The rigidity of the poses conveys an equally rigid interpretation of the event, time, and aesthetic choice of the photographer, opening up a reflection on the complicity of photography in building an archive.

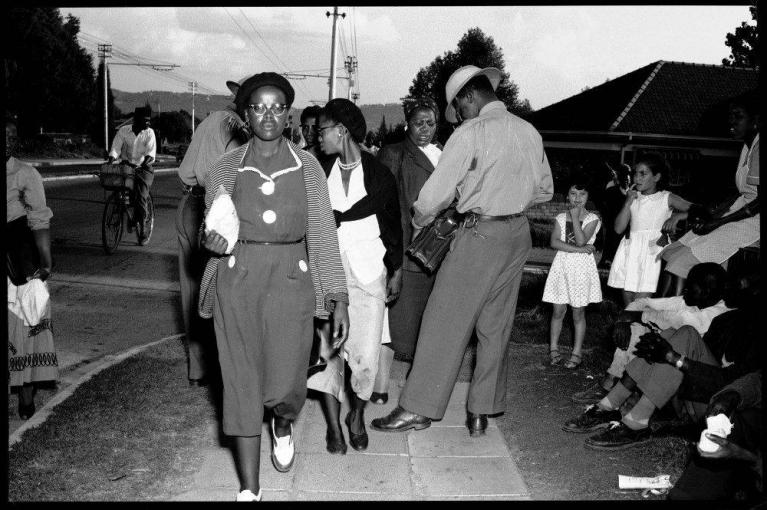

Eli Weinberg, Police check passes and parcels, 1961, Courtesy UWC, Robben Island Museum, Mayibuye Archive.

Women taking a break on the lawns in front of the Union Buildings, Women's March, is the photograph chosen to symbolically represent the year 1956. Twenty-thousand women organized a march to Pretoria’s Union Buildings to protest the proposed amendments to the Urban Areas Act. They left signed petitions, addressed to Prime Minister Strijdom, who was sympathetic to Afrikaner nationalism, at his office doors. A protest chant composed for the occasion became a symbol of the women's struggle in South Africa: "Strijdom, Wathint 'abafazi, wathint' imbokodo" ("Strijdom, now you have touched the women, you struck a rock”). In the photograph, women take a break sitting on the lawns in front of the Union Buildings; they do not sit on the empty benches because they are reserved for Europeans. The archive is also an area of uncertainty in which the sense of guilt and atonement expresses the status of the privileged.

The first color image you encounter is At Durban: But the rickshaw puller is from Zulund. In the photograph, a Zulu man in traditional costume brings a white couple on his rickshaw to Durban town, one hour away by car. The three are posed smiling, looking at a fourth man who seems to be talking to them cordially, a few steps from the means of transport. Zulu men who ride rickshaw can still be found close to the Durban seafront.

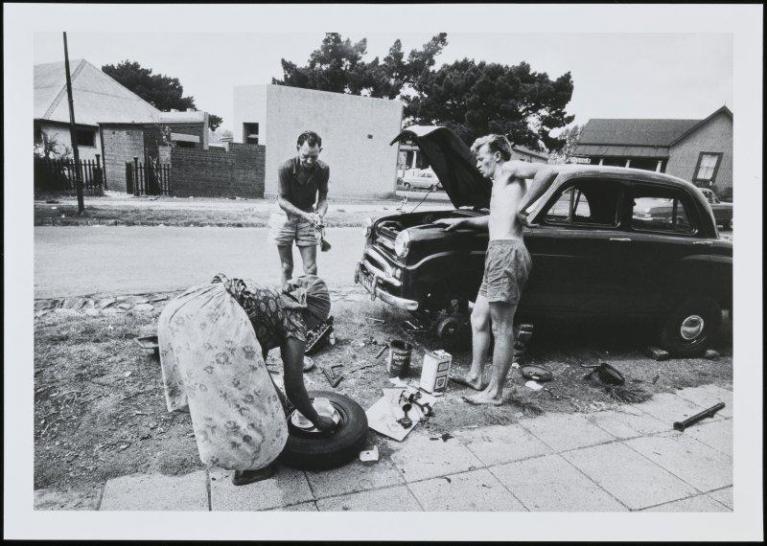

Since 1950, colonial fascism has also been expressed through the law of citizen registration, which established the creation of registers on which the racial details of the inhabitants must be recorded. Each person is classified as "white, mixed, or indigenous, as the case may be." In the photo by David Goldblatt, Afternoon tea being served to two men repairing a car on a sidewalk in Fairview, taken in Johannesburg in 1965, the racial inferiority of a black woman serving tea to two white men is clearly shown.

David Goldblatt, Tè del pomeriggio servito a due uomini che stanno riparando un’auto su un marciapiede a Fairview, 1965.

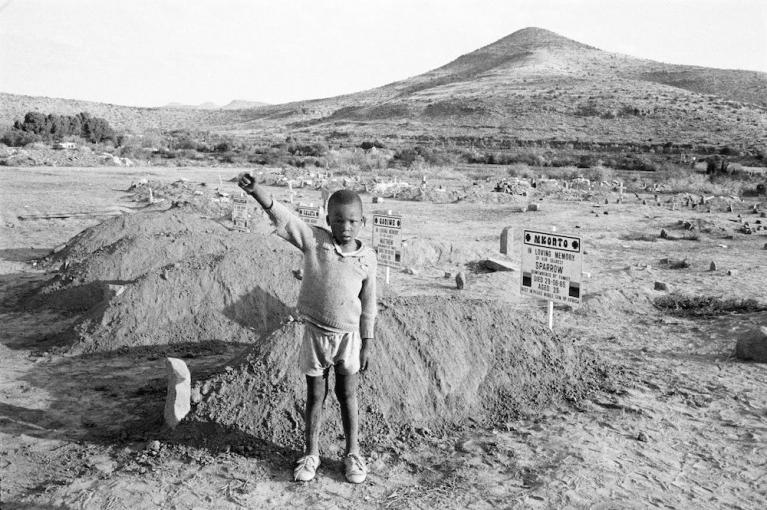

The exhibition continues with the funeral of “The Cradock Four” and the struggles for non-racial politics through boycotts.

David Goldblatt, After their funeral a child salutes the Cradock Four, Cradock, Eastern Cape, 20 July 1985, 1985, black and white photograph.

The narrowest passageway of the exhibition is dedicated to 1994 and the "unconditional" release of Nelson “Madiba” Mandela, when the African National Congress (ANC) took office and Nelson Mandela was elected as the first president of a post-apartheid nation. It seems that the curators, opting for this setup, wanted to highlight the cosmetic policy of the move from a racist state to a confederal democracy, which has not disassociated the new South Africa from the colonial capitalism that has governed the country since the 16th century. This seems to be confirmed by 21st century photographs that are more evocative than actual documentation of events.

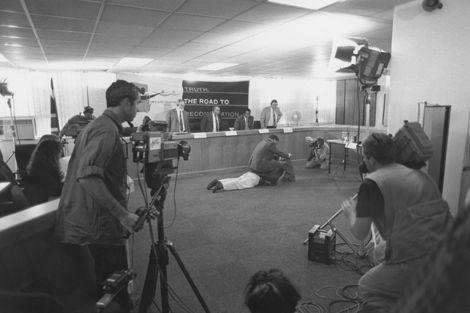

A photograph taken by George Hallett in Cape Town in 1997, Jeffrey Benzien demonstrating the wet bag method of torture at a hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, portrays a security officer showing this method of torture to the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation. The reconciliation of past liberation movements and racism put into action by the Commission for Truth, led by former Archbishop Desmond Tutu, reflects the spirit that animates the new South Africa. Among those who have obtained amnesty for crimes committed before April 1994 are assassins of members of the ANC and other political opponents, right-wing terrorists, members of the Conservative Party and of the Boere Kommando group. This feeling of reconciliation is also fueled by the relationship between white European imperialist settlers and a small corrupted"colored" and Asian bourgeoisie who work with colonial multinational companies.

George Hallet, Jeffrey Benzien demonstrating the wet bag method of torture at a hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Cape Town, 1997.

In South Africa today, white people control almost the whole of the economy, directly and indirectly, and the majority of the excluded population functions as an internal neo-colony. In Italy, the policy of racial integration also translates into the opening of refugee camps, or parts of territory outside the normal legal order, where the legal status of the refugee is questioned (due to the discontinuity between birthplace and nationality). The presence of an exhibition in Italy in which apartheid is censored by the eyes of white colonists, while the last ten years of South African history are documented by historic metaphors of photographers of color, is an evidence of the self-righteousness with which history is turned into an embellished series of aesthetically respectable postcards.

Translation by Laura Giacalone.

A Short History of South African Photography, by Rory Bester, ThatoMogotsi and Rita Potenza. Fotografia Europea XII, Cloisters of St. Peter, Reggio Emilia, from May 5 to July 9, 2017.

Con il supporto di