Speciale

Echoes of Pasts, Inscribing the Present

In an elegantly frescoed salon at New York University’s Florence estate, Villa La Pietra, stands an artifact of beauty, her light brown tunic adorned with brushes of gold fig leaves, a golden collar, and buttons and boots to match. An expansive smile is etched into her ebony face as her body strikes a semi genuflecting pose. Her outstretched arms beckon visitors with an invitation to be served: “give me your gloves, your scarves, your coats, they seem to say.” A similar sculpture but male, is positioned across the room from her. He is made in the likeness of an 18th century page. With the stem of a horn or trumpet tucked under his right shoulder, this African-looking boy, resplendent in rich curls, and brown and gold heraldry, is perched on a descending platform in a posture of obeisance to observers. These figures constitute a broad genre of Western European decorative art – furniture, sculptures, paintings, and tapestries – that portray African bodies in service, as domestic workers, soldiers, porters, and custodians of palatial properties. Known in common parlance as “Blackamoors,” models of this tradition in the Villa’s art collections date mostly from the 17th through the 19th centuries.

Photo by Awam Amkpa.

Our own era is peppered with the resurrections and contemporary renditions of these figures across a variety of media and spaces – from private homes, hotels, and museums, to aspirational fashion and jewelry. The presence of these images pervades contemporary Florence and Venice, (among other Italian locales) to an astonishing degree. Yet their very normativeness renders them unexceptional, even invisible to those who look at them, but do not see. But if we care to see, what do we make of the intriguing but disturbing beauty of these relics that bridge the ages in the Acton Collection at Villa La Pietra? Who made them and why? What traditions of decorative art production and collection do they represent? What material histories and cultural meanings do they encode? How might contemporary scholars interpret these meanings from diverse disciplinary perspectives? Above all, how do artists in our own time re-make these meanings through contemporary works of photography, sculpture, and film? The exhibition ReSignifictions that opened in Florence in the summer of 2015, together with the conference, Black Portaitures: Imaging the Black Body, Re-staging Histories showcases an array of responses to the artifacts and traditions of the European Blackamoor.

Photo by Awam Amkpa.

The exhibition – revolving around 39 mostly sculptural Blackamoors that are seamlessly interspersed with the other artworks in the Villa’s collections, was conceived in my conversations with two extraordinary collaborators, namely Ellyn Toscano and Robert Holmes, who served as the event’s executive producer and producer respectively.

Ellyn, Bob, and I determined to use the “Blackamoors” housed in the Villa as archives and methods for examining art, representation, history and identity. These objects were embedded within centuries-old discourses of cross-cultural encounters and artistic productions shaped by migration, conquest, servitude, and exile. They presented a rich opportunity to deconstruct, compare, and contextualize the myriad portrayals of African-descended bodies that we identify as “black,” in western societies from multidisciplinary perspectives. As such, they constituted an invaluable resource for producing critical knowledge of African and African diasporic identities and representations in European art. Our project aimed to treat the collection as a critical prism through which to examine the iconicity and historical discursiveness of the art collected by the Actons.

As we conceptualized our project, we reflected not simply on the singularity of the objects in the Acton collection themselves, but also on their unique juxtaposition with artworks from different times and places (for instance, the Renaissance set off against the late 19th the century). We wondered at the dialogic ways in which these arrangements frame history and historicity. Art works that do not belong together are put next to each other such as to invoke a non-unitary and non-linear reading of cultural trajectories. We tapped this multivalent framework to structure our exhibition. Shadowed by the burden of history and contemporary politics, of early modern race-making and 21stcentury debates over refugees from the global “South,” the dialogic engagement of art prompted us to ask questions about the discursive function of Blackamoors in global histories and cultures. But we were equally interested in the materiality of the objects themselves – as a genre of African bodies crafted at once as ornament, furniture, and furnishing -- as we were in the consumers who brought them into their homes or added them to their art collections.

Photo by Awam Amkpa.

The many representations of the Blackamoor in public and private spaces, from museums to private parlors, underscore the constitutive role that Africans played in the European imaginary, of the intertwined histories of Africa and Europe via trade, empire, and migrations whether forced or voluntary. As scholars have suggested, the presence of racialized bodies in postures of servitude from the 17th century onwards, may have reflected the pretensions of the mercantile bourgeoisie to aristocratic grandeur harking back to the presence of African retainers in royal courts. Moreover, as cultural theorists have noted, while the bodies and features of these works invoked what we have come to identify as black African, the heraldry, costumes and assorted accouterments in which these figures were cloaked, invoked fantasies of the “Orient.” As an artistic signifier, the Blackamoor, then, was a composite icon that syncretized the entangled histories of European ideas about Africa and the Orient. These project backwards to the history of the Moorish Mediterranean, and forward to European encounters with Afro-Asia and the Middle East through diplomacy, colonialism, and commerce in people as well as things.

Contemporary controversies over African refugees in Europe afforded a particularly timely moment to reflect on the burden of history and cultural coding through art. Within post-colonial African nations, political turmoil, de-territorializations, and conflicts over extractive minerals have fueled an exodus to Europe. These African migrations have brought in their wake, a surge in racism and xenophobia, even as black images in classical art forms have offered a reassuring respite from thorny questions of policy around immigration. At the same time, we were acutely aware of the endangered status of African diasporic bodies in public spaces on our own side of the Atlantic. From the legislative halls of the Dominican Republic to the streets of a Florida suburb or a Missouri town, African-descended peoples faced marginalization and violence. It was impossible not to bring the “New World” into our engagements with issues of race, identity and citizenship raised by the Blackamoors in the Acton Collection.

Photo by Awam Amkpa.

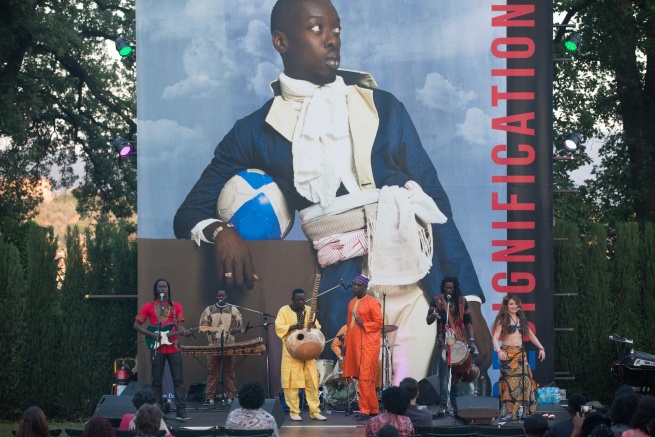

Our project took shape over conversations along these lines at a formal luncheon. There followed a symposium titled “European Blackamoors, Africana Readings,” in which a small gathering of artists and scholars deliberated on the general tone of the project and the artistic and intellectual paradigms within which we could construct an exhibition and corresponding conference. The idea of engaging with the Villa’s Blackamoor collection as ways of reading signifiers of a continuous history from the 17th century to the present, provided the curatorial framework for the exhibition. Our process included a small scale visiting artist program which enabled us to invite some artists to visit the collection, and respond to it through cultural productions of their own. This program also helped define the exhibition’s curatorial direction. In the end, photography, videos, sculptures, tapestry, and paintings produced by 45 artists from Africa, the Americas, and Europe, served as visual texts contesting the conventions within which African and black bodies have been historically objectified. These contemporary artists portrayed such bodies as the subjects of art, thus re-signifying the imagery of commodification that the Blackamoor embodied.

By juxtaposing the classical Blackamoor with reinterpretations of this art, we envisioned the exhibition as a global and inter-generational dialogue between art and artists across time and place. ReSignifications is a conversation among artists from the nations surrounding the Atlantic Ocean, and the islands in-between, who not only draw attention to the original contexts in which the Blackamoors were created, but subvert these settings to contest, complement and contend with the objectification implied by the original. Beyond this work of reflection, revision, and subversion, these artists engage with the contemporary art and cultural activism of each other. These multivalent intersections, and the venues which showcased them, defined the curatorial narrative of the exhibition, ReSignifications.

This event unfolded across three venues spread around the city of Florence: Villa La Pietra, Museo Stefano Bardini, and Fondazione Biagiotti Progetto Arte. Unlike a traditional exhibition in a white cube, the displays in both Villa La Pietra and Museo Stefano Bardini were positioned within the museums’ existing collections. Some of the featured artists included Viktor Omar Diop, Zanele Muholi, Malik Nejmi and many others.

Photo by Awam Amkpa.

ReSignifications is not simply a counter text to historical significations of black/ African bodies as objects in art. Rather, it invoked a vision of art that straddled multiple times (heterochronies) and multiple futures (heterotopia), in ways that challenged systems of signification that codify, ethnicize and arrest human subjects within narrow frames of ‘non-being.’ We questioned not only the stability of canonical vocabularies associated with particular places, but reached for a broader humanism as the wellspring to imagine and produce artistic hemispheres of becoming. We achieved this by putting side by side artists working in a variety of national spaces, who belonged to different generations, and had achieved various levels of recognition, to produce the mosaic that became ReSignifications. Through polyphony and contrapuntal juxtapositions, each work was rendered trans-contextual. Archetypes were rigorously questioned, stereotypes critiqued, and polytypes –signifiers of our fractal beings, imagined. We opened up the genres and conventions of making and interpreting art to scrutiny, scrambled the geographies that provincialized them, and dreamed of multiple and interconnected utopias (heterotopia) and times (heterochronies) in which we questioned one time and place with the other, and sought to fragment their canonical logics and ‘truths’ to produce new, if uncharted imaginaries. In effect, the exhibition was a textual illustration of Edourd Glissant’s ‘poetics of relations.’

The Black Portraiture conference, largely directed by Deborah Willis, provided an intellectual platform for artists and scholars from all over the world to engage with our ambitions. For artists and scholars from the US, the promise and perils of the current state of race relations – the first President of African descent in an age of racialized mass incarceration, for instance, formed the backdrop for talking about a new Pan African hemisphere of social and cultural becoming. For scholars and artists from Africa, the ravages of neocolonialism and ethno-religious conflict, called for new imaginaries of socially activist art. For those based in Europe, the challenges of nativism raised the question whether art could provide spaces of sociality and cross-cultural understanding. With 219 panelists and 43 panels, the conference aptly titled Black Portraitures: Imaging the Black Body, Re-Staging Histories -- extended our method of inter-sectional agency and engagement.

Together, ReSignifications and the Black Portraitures: Imaging the Black Body and ReStaging Histories offers an unusual moment in time that will continue to be a reference point for artists and scholars. The exceptional visions, collaborative energies and resources with which Ellyn Toscano, Robert Holmes and Deb Willis worked with me to produce both projects now would forever be monumentalized with endless gratitude and it surely sets to tone for more work in our immediate futures.

This text is the extract from the catalogue of the ReSignifications exhibition curated by Awam Amkpa.

With the support of