Speciale

Under a different sun / Interview with Lerato Shadi

For Why Africa?, the curatorial collective EX NUNC presents a series of interviews with women artists from Africa and Diasporas, participating in the upcoming curatorial project UNDER A DIFFERENT SUN. This exhibition and performance programme, which took place in Venice in December 2016, discusses topics of lost histories and negated memories from female, diasporian perspectives. UNDER A DIFFERENT SUN is a project conceived and curated by EX NUNC’s co-directors Chiara Cartuccia and Celeste Ricci, in the framework of the third edition of Venice International Performance Art Week | Fragile Body-Material Body, curated by Verena Stenke and Andrea Pagnes.

This third interview in the series features South African multimedia artist Lerato Shadi. Shadi discusses the importance of participation in her practice, and talks about performance interventions as a way to rethink both past and present.

1-EXN: Most of your work explores the limits of dominant historiographical representation. You seem interested in making visible those narratives otherwise neglected, or marginalised by Western culture. Where do your artistic motivations come from?

Lerato Shadi: I think it comes from a personal experience that the World History I was taught about, and the World History I am confronted with, is in fact just Western History. It is finding out that, for example, something as simpleas a World Map—that we all know, use, and take for granted is a gross distortion with racist overtones, as it representing countries and parts of the world where predominantly non-white people live as small than countries and places where predominantly white people live as big. This is one factual example of how Western structures use their power to oppress and miss-represent. You just have to dig under the surface to find many more examples of this kind.

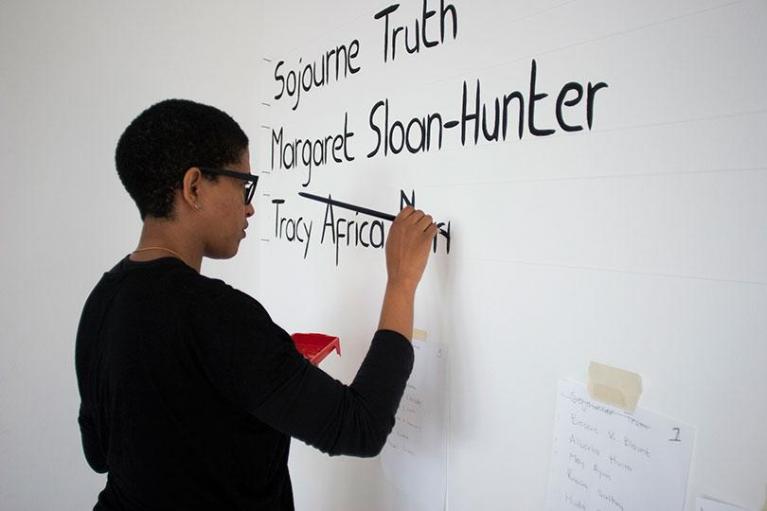

2-EXN: In your work Seriti Se you write names of black females—whose achievements and contributions did not make the selection of History—on the neutral white walls of a gallery. What is your reason to present such a piece in a traditional gallery setting?

Lerato Shadi: To keep on using the example of the World Map I mentioned before, Seriti Se would be me questioning the common map. More importantly,this work exposes our individual complacency within an oppressive system. That is why the audience is asked to complete the work by participating and participating, hopefully,they are planting a seed to undo the ‘map’ in their own minds –while simultaneously making it visible. Usually my work is shown in a traditional gallery setting, a space that represents privilege and exclusion. It serves to challenge myself, and hopefully my audience as well, in how I/we are complicit in the violence of historical erasure by not fighting for a more inclusive and accurate historical narrative. I realised that –by just blindly or lazily accepting an inaccurate history– I would be sanctioning the problematic dominant narrative with my own inactivity.

Lerato Shadi, Seriti Se, performance at Galerie Wedding, Berlin (2015). Courtesy of the artist

3-EXN: Similarly to Seriti Se also the video work Matsogo takes into analysis the mechanisms of construction and deconstruction of history, and how such movements deeply and inevitably alter the essence of past events. The kneading action is accompanied by a soundtrack, which combines two songs from Setswana folktales. Can you please tell us more about this work?

Lerato Shadi: The video work Matsogo is a way of askingwhich are the consequences of the 1884 Berlin Conference. It is referencing what we think we know, what the outcomes really have been and the great complexity of any possible answer to questions concerning this issue. The work looks at the impact that European colonial languages have had on the use of language on the African continent. How the loss of a language is connected to the loss of a history.

4-EXN: Your performative interventions are based on simple, unspectacular actions. In Mosako Wa Nako, you quietly work in the empty space of the gallery for ten days, knitting. The final product of the labour is a red carpet. Why the repetition of the same gesture is so present in your practice?

Lerato Shadi: I guess because I experience everyday life as a series of repetitions. I find that repetition makes it seemingly simple but complex idea visible.

Lerato Shadi, Mosaka Wa Nako, performance at n.b.k, Berlin (2014) Courtesy of the artist

5-EXN: Motlaba Wa Re Ke Namile is a recent video work, which discusses forgotten violent episodes in the history of slavery on the African continent. You have used a disturbing visual language to engage the spectator. What story are you trying to reveal with this piece?

Lerato Shadi: I was reading a lot about resistance and how people have been consistently resisting oppression. This research also revealed that those groups of peoplenormally represented as voiceless had actually spoken aloud and clear. I am interested in how subjectivity, and particularlythe enslaved people’s subjectivity, has been undermined in historical writings. I have also been reading a bit about how Black abolitionist fought and pushed back against this narrative. It is very interesting to noticehow Black literature has not reallygiven a voice to the enslaved people—because they already had one—but rather it has acknowledged their voicesin order to draw parallels to the present situation and make visible those structures that seek to silence not only the enslaved themselves, but also their decedents.

Lerato Shadi, Motlhaba Wa Re Ke Namile, still from video (2016). Cortesy of the artist.

6-EXN: How do you think performance practice can foster a change in the understanding of historical pasts, and eventually in re-thinking historiography as such?

Lerato Shadi: I think of my performance practice as a way of answering the question: “What is a performance?”. I am in a consistent process of finding the answer to that question. Having said that, I am trained as a visual artist and I am a practicing artist. So, I think that contemporary art for me is my way of holding a light to see a little more clearly. Like Alice Walker puts it: “For when we hold up a light in order to see anything outside ourselves more clearly, we illuminate ourselves”. It sounds self-involved but the idea is that meaningful and lasting change starts within the individual. It’s the understanding that the next homeless person you see –or whomever it is you chose to look down on has the same value as Bill Gates– or whomever you chose to look up to. Maya Angelo often quotes Terence in saying: “I am a human being, nothing human can be alien to me”. I think that knowing your history –the good, the bad, the ugly and the in-between– is liberating. And those that misrepresent the ‘map’ do it with the knowledge and the intention of robbingpeople of their history. The objective is not just physical enslavement, but mental and emotional as well. I think, I hope, I pray that contemporary art is in the service of an historical understanding that states: “we are human beings, and therefore, nothing human can be alien to us”.