Speciale

Why Africa? / Under a different sun

The following interview opens up an editorial collaboration between Why Africa? and the curatorial collective EX NUNC, which will continue over the next months on doppiozero.

For Why Africa? EX NUNC will present a series of interviews with women artists from Africa and Diasporas, participating in the upcoming curatorial project Under a Different Sun. This exhibition and performance programme, which will take place in Venice in December 2016, will discuss topics of lost histories and negated memories from female, diasporian perspectives. Under a Different Sun is a project conceived and curated by EX NUNC’s co-directors Chiara Cartuccia and Celeste Ricci, in the framework of the third edition of Venice International Performance Art Week | Fragile Body-Material Body, curated by Verena Stenke and Andrea Pagnes.

This first interview in the series features Gabon-born and Berlin-based multimedia artist Nathalie Mba Bikoro. Bikoro’s research focuses on questions of remembering, narrating, memorialising, and gives form to an artistic practice that aims to de-colonisation of dominant historical narratives, common behaviours and trivial beliefs.

EX NUNC -You once said, with regards to your performance work and your relationship with historical narratives: “We became myths, we became poetry, we became one history in the eyes of the terrorist, in the eyes of the criminal, in the eyes of the winner. We have become the Western fantasy that for so long millions have tried to resist and to correct”. How the negotiation processes with the official history develops through your artistic practice?

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Future Monuments. Forbidden Histories, 2015.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Future Monuments. Forbidden Histories, 2015.

I believe that performing gives us some kind of elasticity of time and lets us become somebody else, hence we see and hear the same stories but they never say the same thing ever again. The dominant narratives and histories have been chosen by the criminals, by the winners, by the bullies, by the terrorists, by corruptions and by our ignorance. Westerns nations, which were newly born, invented stories of primitivism, in order to create a history of civilisation for their own power. It is impossible to create politics without an image and that image becomes a destructive one. But when you learn how to see, you start to observe all the deficiencies of that image and you start to realise all the riches, which were erased within it.

The process of negotiation means to learn how to see and speak differently; in my artistic practice this is a form of cannibalism. The cannibal ingests materials, to transform itself into a different image and to gain new power or energy. The cannibal creates new language, new flesh and new colours. In ingesting it transforms this image into another, and so doing the cannibal systematically changes the social structures it lives in. This process of ingesting, eating and becoming something Other is a process of negotiation, where you reconsider all parameters of your own beliefs of Western history. Ingesting and performing is a creative political act.

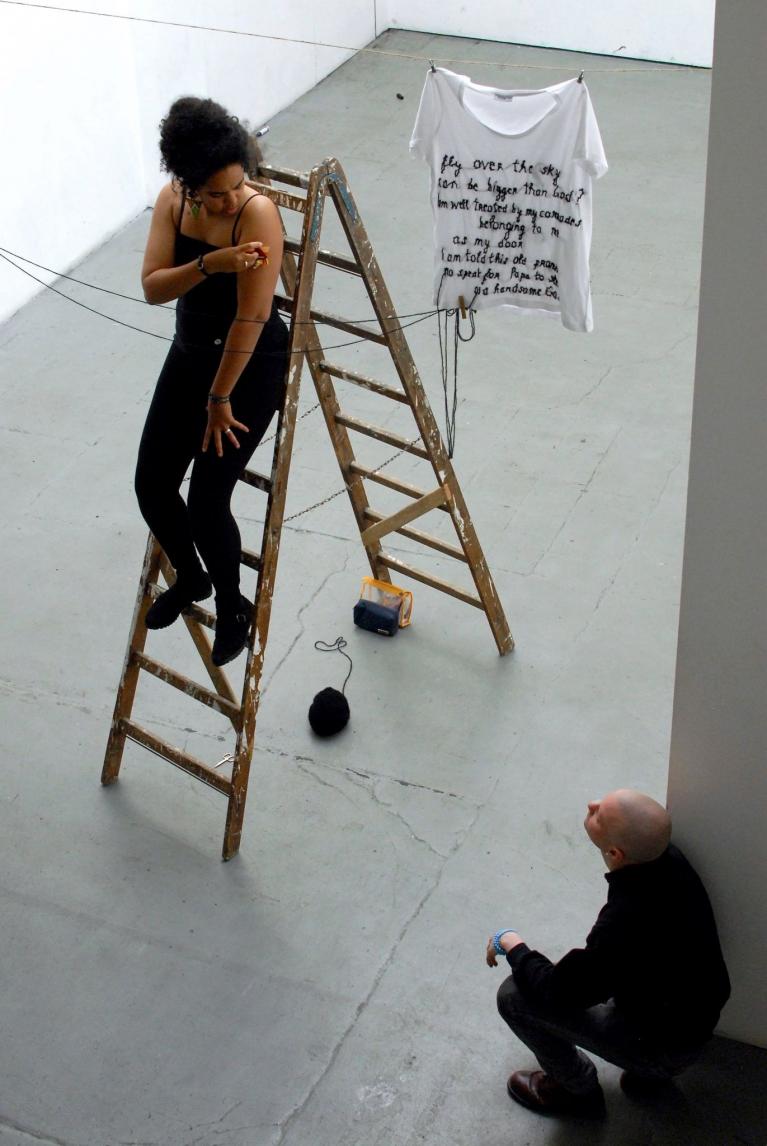

EXN-Central elements of the performance piece, Planting Present Tense, are two t-shirts, on which some words are embroidered. That text plays an important role within your family history. Can you tell something more about that?

Those embroidered on the white t-shirts are words that were written in a letter to my grandmother from my great-grandfather, during the Great War. At the time he was a soldier fighting along with Senegalese Tirailleurs against the German colonial army; he was held prisoner in a very small German labour camp in North Gabon in the region of Woleu-Ntem. At the end of the 19th Century the German colonies had already experimented with the first methods of extermination by building labour and concentration camps in Namibia. These same methods were re-introduced again in Europe in World War II.

During his time as a prisoner in the camp, my great-grandfather was given permission to send a message to his family in the form of a letter. Because he could not read or write, a German officer transcribed his words onto paper. For fear of being punished, my great-grandfather spoke in code so that the officer could not determine the true meaning of the message. It was forbidden to speak about life in the camp or to send any propaganda. The message sounded like it was just a poem: it was written in a way so that only my grandmother would understand. In coded language my great-grandfather revealed that his treatment in the camp involved hard labour, abuse and malnutrition. He warned my grandmother that she would have to prepare to mourn, to fight and to become a messenger. In highly metaphorical language he told her that he would not return. The letter was a suicide note. My grandmother had buried the trauma and grief that she had hidden all of her life until, about four years ago, she told me her story for the first time.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Planting Present Tense, 2015. Photo by Ilya Noé.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Planting Present Tense, 2015. Photo by Ilya Noé.

In Berlin I found an unexpected sanctuary, where I would re-discover and re-live this burial of Grandpapa M’boulou; then I would manifest his and other people’s legacies through past and present holocausts in the project Future Monuments. I find it peculiar that within Berlin’s history there hasn’t been much recognition or memorial performed for the loss of people from Africa and its Diaspora. There is a dangerous unwillingness of the authorities and institutions to recognize this past that has defined our present. A lot of documents about African concentration camps were destroyed by the Germans, nevertheless I found a record of my great grandfather and a photo of him in a prison vest. This is a part of my story that I didn’t know before. I started to dig up information and perform these lost memories. This story haunts my body; it is one to be shared because it is a story about all of us, for all of us.

EXN-You describe your long-term project, Future Monuments, as an investigation about re-inventing the human memorial in the past, present and future. How do you approach the question of monumentality in a performative way?

It is not about monumentality as such, but monument as transient, living and performed. It is the living body that makes things infinite. The bronze statues will always crumble and decay, but the stories told will move in time and foster changes in the way communities are formed and performed. The perception of monumentality only makes monument static. The monument as performance enables us to reconsider what we do with our memories, our voices and how we position ourselves in reality.

Future Monuments is about trying to recollect and to reconcile, trying to heal… to become more human. For me the body, the flesh, holds memory. The body speaks. I use my body because of my experience in childhood fighting Leukaemia. The chemotherapy treatments prepared me. I had seven years of therapy to reconcile with my body. I couldn’t speak and I had lost my memory so the only way that I could communicate was through my body. I still feel that the body is this terrain for history to unravel.

EXN-Your interest in re-thinking monument, beyond dominant Western historical visions, takes also form in your on-going collaborative project Squat Monument. What is your approach towards the city of Berlin, and its way of representing and/or hiding German colonial past?

The project Squat Monument tells the story of the production of World Histories; those are based on colonial systems, which strongly resists also today. Berlin is the mountain of debris that remains. It is also the city that worked as founding machine for the creation of the division of the African continent (Berlin-Congo Conference 1884-1885).

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Demounting Doegen, Performance, July 2016. Photography ©Inês Valle. Courtesy: the CERA PROJECT.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Demounting Doegen, Performance, July 2016. Photography ©Inês Valle. Courtesy: the CERA PROJECT.

I remembered Franz Fanon writing about cognitive dissonance (Black Skin, White Mask, 1952), which brings to the refusal of specific events after a particular trauma. We do not know how to perform our memory and then we end up not knowing how to live in this present. The archives in Berlin still have all the “Kilimanjaro Mountains” with colonial debris spanning over two World Wars. And still a lot of symbols of German nationhood remain, through the older symbols of African-German Empire, while many of these were intentionally erased so that it would no longer be the nation’s responsibility to talk, see or think about it. Yet, it is crucial to see in order to heal traumas. What has happened in Germany and under its colonial templates is also the history of the rest of the World.

As a performer, I took on the task to become a doctor. Each person in this city is a monument. Each has an archive they never looked at before. This is the magic of the doctor: squat and trigger and perform.

EXN-Further to the piece you performed at Cera Projects, London, on the 30th of July 2016, Demounting Doegen, we would like to explore a bit more the reasons behind this work. What inspired you to start this project in the first place? Where did the central idea come from?

Demounting means to dematerialise, activate memory and transmit knowledge, which has been buried by dominant narratives. Demounting Doegen is a performance that is part of my research project Squat Monument. Squatting means to reconsider, change and make visible something that will implant a shift in people’s perception of reality. In order to do this, I decided to go back to the magic of the moving image. It was the German-African propaganda cinema that propelled me into thinking differently about my position in Europe. Many of these propaganda films were notably shot in Berlin; African villages were recreated, while soldiers from French and British colonies were used as background decors and eventually killed during filming. Archive testimonies of German-Afro women, working in the UFA film studios, confirm clearly: “they shot our brothers, 200 of them on the film set movie of Victory In The West” (1943). This was not cinema anymore, it was to become history. And how these films were preserved was to never acknowledge the real histories of these massacres.

By the Second World War, the participation of Africans became fewer and their voices were removed from the films. However, before and during First World War period their presence was much more prominent in cinema, and African women had leading roles –even though their characters often were subdued to African stereotypes to re-enforce the idea of Germans’ superiority. Germany pursed many colonial projects during this time, also outside the cinema industry. Universities and museums worked together to create their own knowledge of an imagined Museum Of World Culture. That knowledge was to be transmitted and produced only by men, as women were believed not to be cultural producers of knowledge. Scientists or pseudo-scientists used the many colonial camps of African and Asian prisoners of war from French and British troops to exercise these criminal anthropologies.

A linguistic called Wilhelm Doegen recorded voices of many of these prisoners, men and few women. His focus was on pronunciations of different languages, without any concern towards the content of what was actually being said. The recordings were exhibited in galleries and fairs: messages for help, personal stories and, jokes where heard. Through the voices of the male soldiers, women re-appeared as mothers, wives, daughters and sisters. Over 5,000 of these recordings exist and most of them are held in a small basement room in Berlin, at Humboldt University. What interests me is how the image of women emerges. Demounting Doegen is a suggestion of how to hear voices, which talk about a violently suppressed history. Doegen becomes a symbol also for systems still in place, which need to be changed. These systems have become landmarks and monuments dominating our way of thinking and making, while performativity enables us to initiate the process of demounting these colonial myths.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro in collaboration with Anaïs Héraud, Squat Monument, 2016. Photo by Kinga Michalska.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro in collaboration with Anaïs Héraud, Squat Monument, 2016. Photo by Kinga Michalska.

EXN- Your investigation into the archive is crucial to the work you are carrying on with Demounting Doegen. How do you approach the archive, as a traditional instrument of dominant and partial Western historiography?

The task of the archive should be to de-modernise and grant accessibility to the community that produces it. The inconsistency is triggered by the categorisation and ‘boxing’ of memory, which ultimately needs to be performed one way or another to make pasts visible and bring them back to cultural knowledge. An archive must move at all times. It must generate new questions, new architectures and archaeologies.

Working with archives, one realises that those holding them do not know what to do with this information. There are images being seen for the first time, texts being read for the first time and the digitisation of these documents often does not guarantee the preservation into the future. Preservation means that you have to make things visible, but in this very traditional practice most of the time these materials do not move to the community that produces it and transforms it. The feeling I have when I work with archives is that I am inside a burning house. Every image, texts or sound inspire a memory, an own personal biography, and activates my body to respond to it. It is an endless conversation with ghosts. Everything is a story. Everything is a myth, and only with this myth you are allowed to create, to position your identity and to understand other truths.

The archive is not a product of Western historiography, but the practice of its preservation most definitely is. I say this because archive can be other materials, voices and stories from your family passed down to you. You cannot find them on Google but you can travel to them in the middle of the rainforest. Archives entitle you to travel to the unknown, in a process of constant returning.

EXN-How do you think performance practice can foster a change in the understanding of historical pasts, and eventually in re-thinking historiography as such?

Currently my practice, notably in the project Squat Monument, is to activate and reconsider the role of archives, of knowledge and how community transmits it. Inevitably this leads to significant shifts in social experiences. An archive can only be sustainable if there is a community to activate it.

Historiography itself is a dangerous anthropology. In a traditional historiographical perspective, history becomes hierarchical and chronological, and this is the limitation of archives. Performing pasts, memories and debris can inspire a reconfiguration into the rhyzomatic relationship of time, places and events. History is stories that make people move. Some of these stories are based on facts, but do not tell truths. Some of these stories are myths, but make truths visible. The performing body creates an open system of thoughts and actions, by interweaving voices, images and events as a constellation connected to different people, spaces and times. The task of this body, of this myth, is to transform the archives into a Hydra body of many heads moving across land and water, whose image is created by the knowledge being produced through various cultures.

By retelling the stories with your own voice and body, you create spaces of decolonising knowledge, which will foster significant social shifts in our communities.

Squat Monuments, video-essay by Nathalie Mba Bikoro and Anaïs Héraud, trailer.