Speciale

Anti-chronological gaze on history through contemporary art / Field Work

Artistic Responses to History Problems. Field Work at Tiwani Contemporary.

As a very young schoolgirl, I remember being highly fascinated by my history course books. In them, texts were combined with colourful visual apparatuses. Cartoon-like drawing of men and women, standing by a fire in a cave, slowly evolved into images of warriors, kings and stereotypically depicted thinkers, as the years passed. Coming to the end of primary school, the first blurry photographs started appearing on the pages, silent proof of more recent events. Going through those books was like moving back and forth from deep fantasy to reality, slowly and continuously overtime. History classes were my very favourite ones; they involved a kind of magic storytelling, which confused fiction and facts, in my childish ears and eyes. Growing older, I preserved my passion for this subject, which rapidly transformed itself into a discipline. But, as time went by, something changed in my approach to history as an object of interest. Impressions left place to certainties, my ideas became less flexible, my gaze narrowed. I started detaching that writing and telling of the past from fantasy and imagination. I began confusing biased words, now written on heavier and increasingly difficult books, with unproblematic truths. I was made to believe that reality was, and had always been, just one. The time of history finally assumed the shape of a line, constantly moving forward in a pacific, consequential manner.

Later on, visual and performance art will come to teach me otherwise.

Theo Eshetu, The Mystery of History and My Story in His Story (2015), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Theo Eshetu, The Mystery of History and My Story in His Story (2015), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

The London art gallery Tiwani Contemporary is currently showing Field Work, a collective exhibition featuring eight artists from Africa and diaspora “who have anchored their practice in a deep examination of the mechanics of history”, as the press release states. Browsing the fairly small space of the gallery, the visitor will in fact face eight distinct and very peculiar approaches to questions of time and history telling. The chosen artworks bring to light alternative ways of recording, recovering and study the many forms of the past, while challenging dominant Western-centric historiography. Each of the pieces is expression of much more complex artistic researches that can, in some cases, reveal relevant connections in terms of methodology and underlying point of interests.

-Archives-

Both the works of Theo Eshetu, The Mystery of History and My Story in His Story (2015), and Katia Kameli, L’Oeil se noie (2016), choose photographic archives as objects of analysis. In the case of Eshetu, the archive in question is that of former Yugoslavia president Josip Broz Tito. Eshetu departs from an official, public collection of visual material, in order to recompose a history that is deeply tied to the personal story of his family, as the artist’s grandfather served as Ethiopian Ambassador in Belgrade, between 1966 and 1970. This work casts a new light on the politics of Cold War –thanks to the peculiar perspective given by the artist’s double bound with two of the countries participating in the Non-Aligned Movement– while disclosing forgotten details of a distant familiar past.

The archive approached by Katia Kameli’s is just the chaotic collection of photos and postcards of an Algerian street vendor. Mr Azzoug’s street stall has preserved its place in the streets of Algiers over the last thirty years; its repertoire of fragmented visual memories gives shape to an alternative iconography of Algeria’s history, during and after colonial times. Kameli’s work overcomes the distinction between official/public history and personal/minor narratives, and so doing it fosters alternative understandings of the past and its historiographical representation.

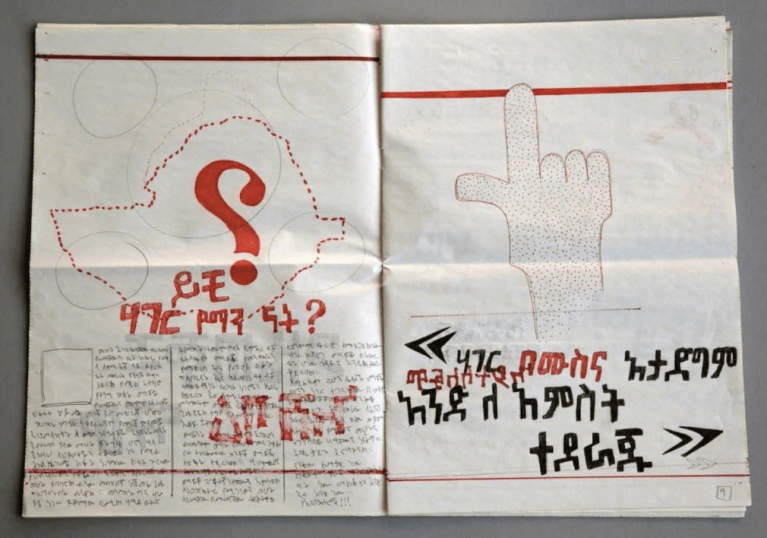

Robert Temesgen looks at a different sort of archive, one made of supposedly fleeting written words, so to put into question the position of the written document in the construction and transmission of information. In his piece Another Old News (2016), Temesgen uses social media to collect subjective accounts of old news stories, and compile them into a series of handwritten newspapers. The work examines how the overlap and confusion of official accounts and personal recollections direct our interpretation and awareness of events from recent past.

Katia Kameli, L’Oeil se noie (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Katia Kameli, L’Oeil se noie (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

-Objects-

The very distinct works of Rita Alaoui, Thierry Oussou and Abraham Oghobase all declare an interest in objects and/or artefacts from the past, as only possible bearer of those particular memories that elude archival classification. Rita Alaoui uses the methods of anthropology to build up her personal collection of specimens: fragments of mineral or organic materials gathered on the beach and in the forests surrounding Casablanca. These little objects, which are the last remains of past ages and extreme witnesses of time and its effects, become the subjects of the drawing series Object Trouvé (2014-2016). With a similar spirit, Thierry Oussou’s paintings, Untitled (2016), take inspiration from proto-languages and pre-historical signs, here loosely reproduced in an attempt to restore long forgotten calligraphies. But the most interesting of the three is maybe Abraham Oghobase’s Ken Saro-Wiwa Pipe’s (2016), a work that combines archival digital prints and sound. As the title suggests, the protagonist of the piece is an ordinary object, namely a smoking pipe from the personal collection of Nigerian writer and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. The inanimate object becomes something more than an empty relic: an exclusive witness of history, as effective in its role as a lively picture of Saro-Wiwa himself. The combination of the simple scan image of the pipe, which doesn’t save any room for further comment, and the soundtrack that resonates with echoes of the past, opens an unexpected window on a precise historical narrative.

Robert Temesgen, Another Old News (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Robert Temesgen, Another Old News (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

-Questions of Time-

A critical reflection on history and historiography cannot be sustained, without an organic investigation of the structures and rhythms of time. Therefore, each of the works presented in the exhibition reveal a pertinent analysis of such questions. Nevertheless, two artists in particular seem to choose the texture and (im-)materiality of time as central object of research: Kitso Lynn Lelliott and Youssef Limoud. Kitso Lynn Lelliott’s intimate and poetic video piece, I was her and she was me and those we might become (2016), engages in a reflection on non-linear time. In the work, distant timelines come together in fragmented and mutable constellations. The artist underlines the impossibility for a valid historical narration, personal or collective, to come as a single, immutable object of knowledge. History is the result of a continuous interweaving of plural and dissonant accounts. It is an irreducible complex of traces, impressions and dreams.

Thierry Oussou, Untitled (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Thierry Oussou, Untitled (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

The sculptural installation Ruins (2013-16) closes this exhibition overview. Youssef Limoud’s series inquires into the relation between architecture, landscape and the flow of time and events. These sculptures seem to appropriate the methods of material cultures studies and archaeology, in order to re-discover the traces of decay and loss in the physicality of the ruins. Although, Limoud’s sculptural representation of architectonical ruins is not inspired by ancient debris of the distant pasts, but rather by the current destruction taking place in Middle-Eastern war zones. Also in this case, present and past collide and confuse, in the anti-linearity of time.

Abraham Oghobase, Ken Saro-Wiwa Pipe’s (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Abraham Oghobase, Ken Saro-Wiwa Pipe’s (2016), Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.

Field Work –open until the 25th of February 2017– is a simple exhibition of difficult works, products of sophisticated artistic practices. The personal researches of the artists involved all attempts to grasp alternative ways of talking time and times, of investigating stories and histories normally neglected by western Historiography (with a capital “H”). The final aim is to reconfigure the methods of historical thinking, in the light of a comprehension of time that is anti-chronological and anti-hierarchical, so to create the possibility for alternative knowledges to emerge and spread. For the visitor, a walk around the artworks featured in Field Work is an occasion to sharpen the gaze and become acquainted with narratives of the past that, although marginalised or forgotten, survive in the present and continuously act on our contemporaneity.

With the support of