Speciale

Body Talks in Bruxelles

Here the column's introduction: Why Africa?

“May the spirit of Patrice Lumumba and other murdered leaders who live in the Kingdom of Heaven take care of the ghosts of King Leopold and others of his ilk,” kept on shouting artist Tracey Rose in the streets of Brussels. Dressed in a tunic smeared with paint and accompanied by a totem made of dry branches, she was condemning the massacres and wrongdoings committed by King Leopold II in Congo during the colonial period (Tracey Rose, Tracings, 2015).

Tracey Rose, Tracings, 2015

Intense, cutting, provocative and highly political, this exhibition curated by Koyo Kouoh at Wiels in Brussels showcases the work of a generation of female artists from various regions of Africa who were trained in the late 90s, twenty years after post-colonial studies and the radical body-art performances of the 1970s, when the issues of feminism, gender and sexuality were being revisited and questioned by contemporary art practices. It no longer brings out the emotion, expression and “passion” of the Western body – the symbol of a century of turmoil, restlessness, atrocities, desires and madness – but focuses on the warmth, memory and sensitivity of the 2000s African body, with its multiple identities, vulnerability, stories and rebellions. Unlike Western countries, the public exhibition of the naked female body as a means to point out social injustices is still a deeply rooted practice in traditional African culture.

As this exhibition brilliantly shows, the relationship between art, body, feminism and sexuality has become increasingly complex and rich, with new narratives, perspectives and influences from other countries, cultures and geographies re-writing the history of art. The great “book of art” necessarily had to come to terms with diasporas, migrations and homecomings, and with a whole new “cartography” to be discovered and re-read. Many of these female artists were actually forced to leave their countries and came back after long wanderings in Europe and America, bringing back with them new cross-cultural influences, differences and hybridizations (as in the case of “Afrikaans”, the language of Dutch settlers in South Africa). Becoming an active and integral part of the history of art, these artists – and the rest of the non-Western world – provide unusual insights and perspectives, subverting dusty and outdated theoretical, social and cultural paradigms, unable to reflect the radical ideological and political change affecting the female body outside the Western world.

Through a series of installations, collages, photographs, sculptures, performances and experimentations focusing on the body and its material dimension, these six African women artists, each with her own style, technique and themes, give new voice to a historical, militant, intimate and political body that bears the signs of pain, violence and suffering – as well as of awareness, courage, strength and resilience – inscribed within its flesh.

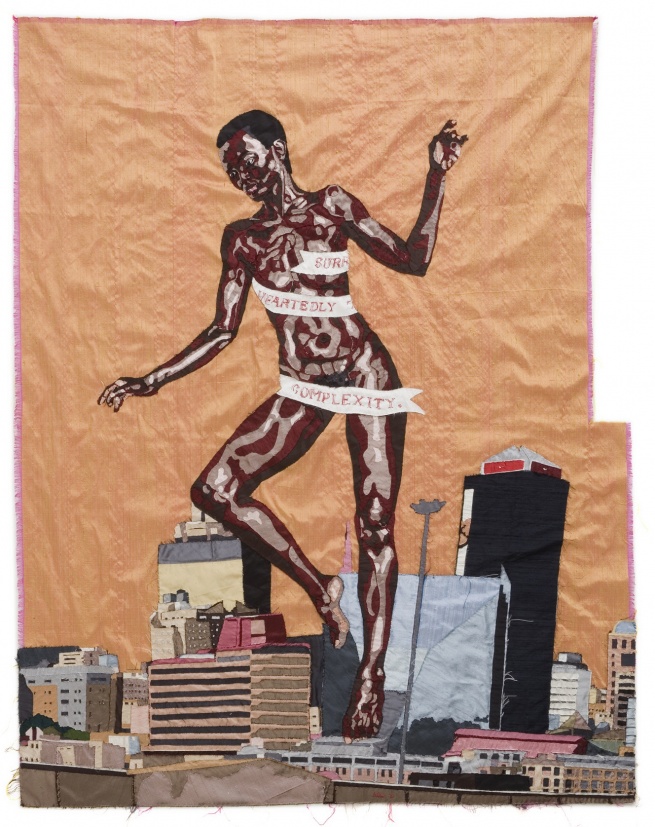

Rather than from a shell driven by the breeze of Zephyrus, a “Black Venus” emerges from the concrete and glass skyscrapers of Johannesburg (Billie Zangewa, The Rebirth of the Black Venus, 2010); “The Three Graces” replace their light, transparent veils with polyester threads, rugs and Afro acrylic wigs (Marcia Kure, The Three Graces, 2014); Nymphs, Muses and Venuses in lascivious poses are not portrayed on smooth, neat surfaces, but appear from cuts, tears and overlapping materials (Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Nues, 2014). Alongside this “subversion” and re-interpretation of classic iconography carried out through new techniques, treatments and materials, and above all through each artist’s in-depth critical view, the exhibition is enriched by two very different and striking performances by Ivorian artist Valérie Oka. Inside a sinister and austere iron cage are a red hammock suspended about a meter off the ground and an erect phallus made of clay (Valérie Oka, Untitled, performance / installation, 2015). In the silence of the room where the cage is placed and the stillness of the objects that inhabit it, the body of a woman curled up in the hammock slowly begins to move. Stretching her arms, legs, and eventually her entire body, Lazara Rosell Albear gently comes out of her “shelter” and starts walking in the cage. It is only a few, simple, repeated gestures, not accompanied by words, in an intimate, highly introspective atmosphere. The naked woman looks straight ahead without casting a glance at the viewers, walks through the iron fence, reaches the phallic sculpture and touches it with one hand; then returns to the center of the cage and gently slips back into her fabric cocoon. The performance ends with this disturbing image of the female body as an object to be used and abused by the male gaze.

From left: Billie Zangewa, The Rebirth of the Black Venus, 2010; Marcia Kure, The Three Graces, 2014 and Valérie Oka, Untitled, 2015

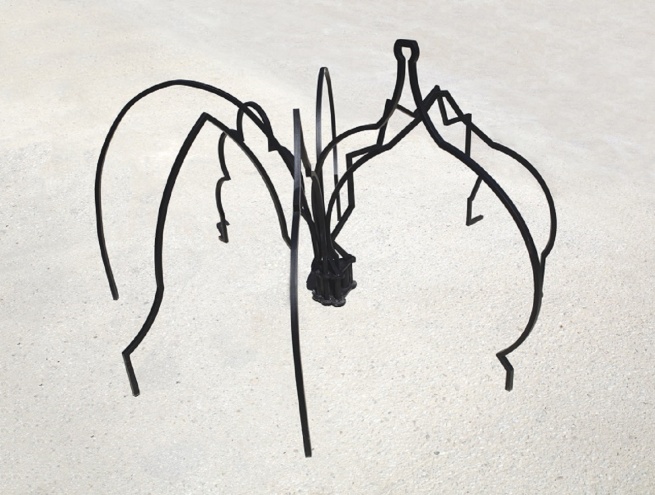

In our imagination, the phallus has become an established symbol of patriarchal domination, as theorized by Freud and Lacan and later suggested by a number of great female artists focusing on women and their obsessions, such as Louise Bourgeois (whose Maman also inspired Algerian artist Zoulikha Bouabdellah’s work L’araignée in 2013, exhibited here in a “smaller version” in steel), Carol Rama, Maria Lassnig, Sophie Calle and Nancy Spero. In a sense, we have “metabolized” the marks left on the body by the extreme actions performed by Gina Pane, Carole Schneemann, Valie Export and Hanna Wilke; and we took part in the acts of rebellion and protest started by Ana Mendieta, Regina José Galindo and Tania Bruguera. However, we still lack the necessary critical-historical distance to clearly focus on the controversial image of African female body and the political relevance of African contemporary feminism. In the introduction to the exhibition, the curator poses a critical question to herself and to us: “What is an African female black body? Is it the supreme object of patriarchal sacrifice? Is it the sacred, stained body, transgressing the boundaries of race and gender in the way it stages and embodies history? Is it all of the above?”

Zoulikha Bouabdellah, L’araignée, 2013

Zoulikha Bouabdellah, L’araignée, 2013

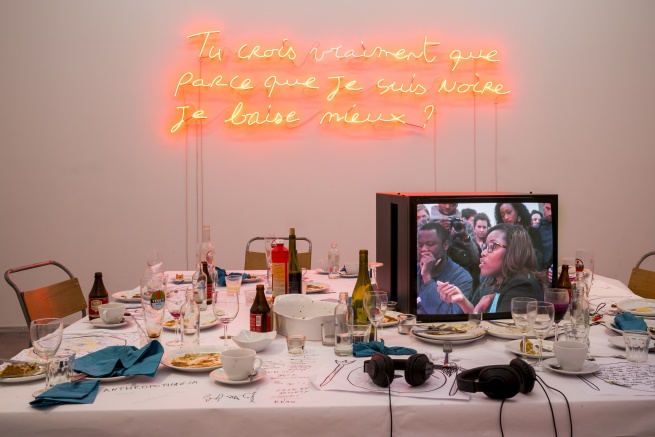

After leaving the noisy silence of the iron cage (Oka’s performances were held at the same time in different rooms, recorded and then played back on a TV screen), we come across the visible, and yet immaterial, remains of a “last supper” consumed by the artist’s “guests” through provocative statements, questions, debates and reflections on these and other questions. Gathered around a table, the twelve diners (including the artist) dealt with many controversial issues, related to current and past events, such as the status of women in post-Apartheid South Africa; the atrocities perpetrated in more than a century of British, Dutch and French colonialism; the self-immolation carried out by many African women in the 19th century not to be traded as slaves by the Arabs; the impact of capitalism on Kenya; and the profound significance of African women’s art. Along with the remains of coffee and food, and the notes, drawings, scribbles, thoughts and words written on the tablecloth, these unusual “guests” also left a unique set of emotions, feelings, memories, tensions and provocative statements “encrusted” on plates, glasses and cutlery (Valérie Oka, En sa présence, 2015).

Valérie Oka, En sa présence, 2015

Valérie Oka, En sa présence, 2015

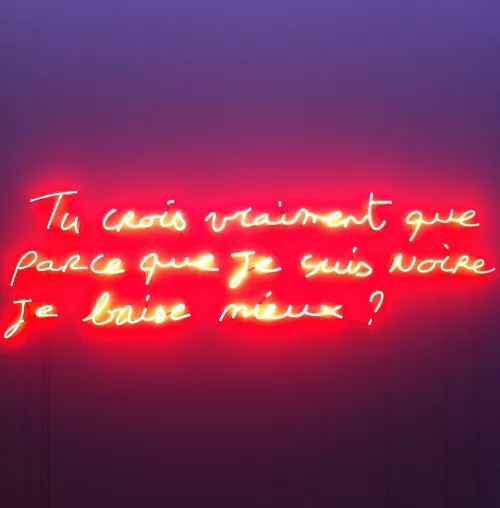

This performance – which appears as a discursive, empathic and narrative counterpoint to the introversion of the “cage”, and has also become an installation – re-writes Nochin’s provocative question “Why have there been no great female artists?” with the frankness and straightforwardness typical of African culture: “Do you really believe that I fuck better because I’m black?” – which ironically and provocatively winks at Western man and society [Fig. 7].

The Exhibition: Body Talk |14.02-03.05.2015 @ Wiels | Centre d’Art Contemporain, Bruxelles.