Conversation with Daniel Blaufuks / Missing present

Laura Gasparini - Almost all your work is based on memory and the various forms that it encloses and represents. Do you think photography is the most suitable language for working on the concept of memory?

Daniel Blaufuks – Not really, I think literature and some cinema are more suitable, since they demand from the viewer a larger span of attention and immersion. Nevertheless, photography is already memory by its own essence, so memory is inherent to the photographic process.

LG – In This Business of Living, you make a clear reference to the literature, particularly to the diaries of Cesare Pavese published under the title This Business of Living. What has struck you for that work?

DB – Well, Pavese is a wonderful writer and his diaries are beautiful in his musings of everyday life, which I am very interested in. The word mestiere, which does not translate well into English, speaks of this necessity to live, to reinvent life on an everyday basis. This can be a difficult task at some times and for Pavese it ended tragically with his suicide. The last annotations in his diary are to the point, but also on a day where he just writes: “today, nothing.” So, at a time when I had my own sorrows, I worked on a series of photographs that related to this idea of time unfolding day by day. Later it was an exhibition, even later a book, and is, to a certain extent and along with another writer Georges Perec, also the basis for the series “Attempting Exhaustion”

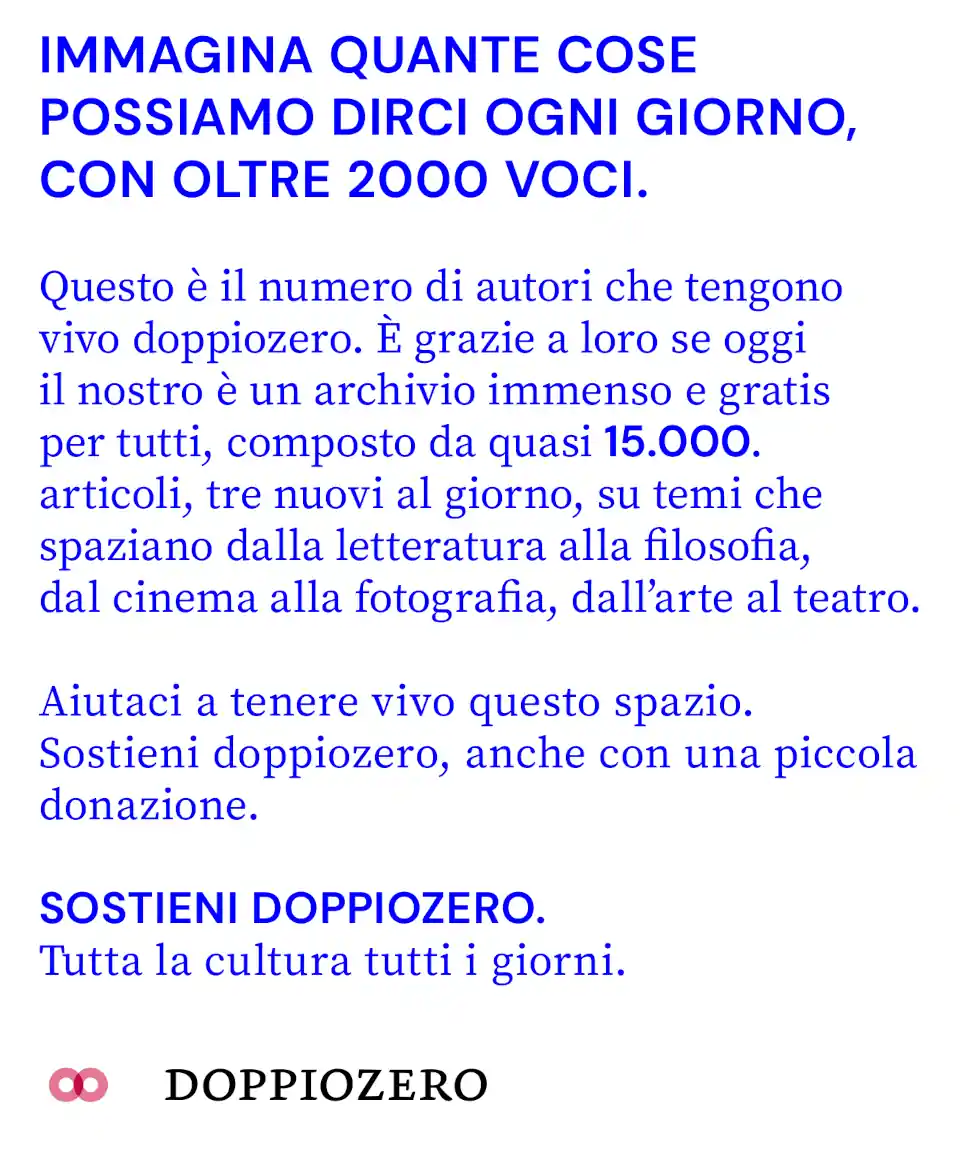

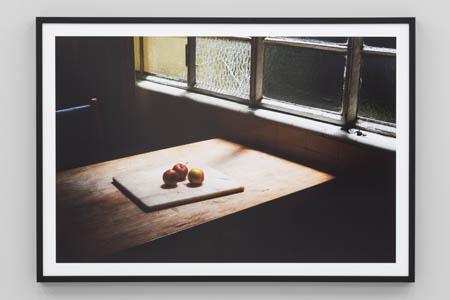

LG – Some images of this project are real Still Lifes that have the charm of those of the seventeenth century, which behind the formal aspect hide deep meaning and symbolism. Is it so also for your pictures? – Some images of this project are real Still Lifes that have the charm of those of the seventeenth century, which behind the formal aspect hide deep meaning and symbolism. Is it so also for your pictures?

DB – Yes, I am interested in a kind of photography that has some depth and meanings beyond its surface. I am certainly not keen on photographs that only are what they seem to be.

LG – Literature, the word is very important for you. Sometimes it is a strong mediation with reality. I am referring to your project on Terezín from which you started from the collection of W.G. Sebald to go then to investigate those places of memory.

DB – The meanderings of literature are platforms from which you can project thoughts and images. When a writer, such as Sebald, uses photographs as well, many other possibilities of images are born. In Terezín I followed one of many possible paths starting with one photograph published in his last book Austerlitz. The image was made by a German photographer Dirk Reinatz in the former concentration camp of Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic and that path took me in the end to make my own book about it.

LG – In your work you also use other forms of memory such as historical photographs, anonymous authors that you extracted from the archives life to assign other meanings, other reading modes.

DB – Every image can have many possible readings, according to where, when and by whom it is seen and by whom it is distributed. This is the danger of photography, that the same image can be used for all types of information, that it can be misused, misquoted, altered, reframed, etc. One should handle this fragile material with extra care and that is what I try to do.

LG – Many exhibits are made of different materials: words, posters, historical photographs, objects and of course your photographs. I refer in particular to the exhibition at Toda a Memória do Mundo, Part One (All World Memory, Part One). However, it seems to me that you prefer the form of the book, the notebook, the diary, an object held in your hand, and it comes with its own times of perception and reading.

DB – An exhibition is something very temporary and geographically quite restricted, while a book can last and can travel. A book is democratic because it can be more easily accessible than an artwork. The book might be the greatest invention of mankind. It is public and private, it can be seen in a café or in a library. It can be given as a gift. It is a memory in itself: where did I get this book, where did I read it first, what is this piece of paper I kept inside?

LG – Going back to the places, looking at the past, as Gaston Bachelard says in The Poetics of Space (La poétique de l'espace) allows to recreate a poetic image that is not the echo of the past, but a projection in the future. Do you find yourself in this statement?

DB – There is nothing but past and future. In fact, it is the present that does not exist.

LG – You have often declared that photography is a highly subjective medium and in this respect you appreciate the uniqueness and poetic aspect. Are you a collector?

DB – I am more and more a collector of immaterial things, but, yes, I am attracted to many objects, because of its past use, of their form, and of their beauty. But I refrain from collecting, since I don’t have the space one needs for that kind of serious hoarding.

LG – You recently exhibited at European Photography in Reggio Emilia's part of your work Attempting Exhaustion inspired by George Perec's book, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris where the writer observes the marginal aspects of reality in Place Saint-Sulpice, the infra ordinary. Even Cesare Zavattini, through the poetics of qualsiasità/everything, supports the opportunity to find interesting things anywhere in any subject. Poetry that found a fertile field also in the work of Paul Strand of Un paese in Luzzara and later in Luigi Ghirri. A truly singular coincidence.

DB – The coincidence lies in the fact that we are all searching for the same thing: a reason to live within ourselves without being overtaken by the speed of things around us. That is the poetry, to stop for a single moment and breathe in and out.

LG – The narrative capacity of photography is important to you. Did you even approach the language of the movie and the video?

DB – Yes, I have done a few films and video work. Even the Terezín project has now two works with moving images: Theresienstadt (2007) and As if (2014-2016), which is a film lasting almost five hours. One needs patience…