Speciale

Interview with Mugendi K. M’Rithaa / African design

“Until lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter”

The Nigerian proverb

lettera27 and Mugendi K. M’Rithaa met in Milan, where he came for his presentation at Meet the Media Guru: Future Ways of Living series in collaboration with Triennale of Milan that took place at the Fabbrica del Vapore. The below interview is the result of the passionate conversation between Mugendi K. M’Rithaa, Elena Korzhenevich, Adama Sanneh and Tania Gianesin. A special thank you to Anna Barbara and Luca Poncellini for providing us with some stimulating questions for the interview.

Elena Korzhenevich: You are the curator of Design Indaba, one of the most important festivals of creativity in Africa, can you tell us about the vision behind Design Indaba?

Mugendi K. M’Rithaa: Design Indaba is hosted every year and has been running for the last 22 years. I have been specifically curating the industrial design section. What I know of Indaba, which is an institution I have a lot of respect for, is the realization to that we know very little about the creative potential of Africa. It’s about bringing the creative talent into Africa for the benefit of the African creative industries, but also about showcasing the emerging creativity from the continent. In that sense it’s a very important platform that brings international and local designers together (and when I say local I mean African, not just from Cape Town or South Africa) into a space that is dialogic. They host an on-line platform where they constantly push the idea of what is a good design, they sponsor something called “The most beautiful object in South Africa”, which can be an app, a chair or even a piece of knitwear inspired by a local culture. It’s really about bringing a certain sensibility and understanding about what is actually happening on the continent from the creative point of view.

Mugendi K. M'Rithaa.

Mugendi K. M'Rithaa.

EK: Why do you think today, after all these years of activity, there is still so little awareness of African design here in the West? What obstacles have you encountered in spreading the message and telling the world about it?

My understanding is twofold. I think part of the problem lies in Africa itself, we have not told our story sufficiently. To reference the Nigerian proverb: “Until lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter”. There is a sense that the African designers and creatives may not have had as much confidence in their own creativity and so we tend to mimic and praise that which comes from elsewhere. That’s the first problem. The second problem is the stereotypical view of Africa on the part of the global audience, which does not expand the understanding that Africa has much more to offer than crafts. A lot of what is seen as African art or design is still seen as very rudimentary crafts, set in traditional and ethnic kind of labels. And every time an African designer tries to break away from that and move into something much more modern and cosmopolitan people want to push it back towards the ethnic.

EK: You have just anticipated one of our questions: why do you think the global audiences tend to promote the idea of African design as some kitsch exotic souvenirs instead of telling the stories of the aesthetically powerful objects you produce every day?

Sibusis Brian Mokhachane, backpacks, Accessories designer and Social enterpreneur, South Africa.

Sibusis Brian Mokhachane, backpacks, Accessories designer and Social enterpreneur, South Africa.

With the risk of oversimplifying things I would reduce it to two words: the first one is ignorance. No one told them better, they don’t know about the richness that is out there, that is why the role of organization such as yours is so important in giving them an alternative view of the world and of Africa within the context of the world. The second word is arrogance, which to me is the refusal to accept that something brilliant, exciting and out of the box is coming from the continent. Ignorance we can help, by bringing the information, arrogance can only be met with force, since it means that no matter what we say, you have already made up your mind and you are not going to listen.

EK: Do you think it makes sense to talk about African design? What is African design?

No, I think Africa is too big a place to reduce it to an African design. Even a country like Italy, small by African standards, has such an enormous variety from one city to the other, so for one to reduce Africa to one idea or to one stylistic representation is wrong. One could speak of elements of African design, where there is commonality, like the rustic use of earth colors and materials which are earth-friendly, the use of pattern or color, those are common across the continent, but I cannot with all clear consciousness say that there is such thing as an African design or African style. I think that would be an insult to the creativity of the continent with over a billion people and 54 countries, I think it’s too rich to reduce into one thing.

EK: I guess it’s like saying a “European design”, what does it even mean?

Precisely. If you take an IKEA design and call it a European design it would be an insult to many other design traditions. It’s coming out of Europe and it has a very clean aesthetic, but that is not to say that this is all that comes out of Europe. And this is a personal challenge I have, to be the one who has to defend the continent occasionally.

EK: If you had to suggest some key words and themes that Africa can suggest us to face the next millennium what would they be?

One theme would be informality. The idea that things don’t have to be formal for them to be considered a form of art or design. Second thing is hackability. The idea of hacking, mixing, re-purposing, making things work from old and new, mixed, West and Africa mixed. Another element is hybridity. It’s the idea of not pursuing pure forms, but having a pragmatic mix. And then there is authenticity, which is about not hiding the pieces, for instance if there is a piece of wire in the design, you can see it, it’s not transformed into something you cannot recognize, it’s a pure expression.

EK: Time is one of the parameters of design. At the moment there is still a disposable design and at the same time the design that repairs. A design that produces trash/waste and design that is born of that waste. Which model does the African design have and which one does it want to follow?

The truth of the matter is that it’s both and it’s born out of necessity. The hackability, the recyclability, the informality is the reality that most Africans live with. Of course there are still Africans who can afford to make fresh furniture, so it’s not just about recycling ore reusing of what exists, but it’s also about creating newness. So it’s both, but if I had to give percentages it would be 20% of the newness and 80% of recycling and that is out of necessity.

Madri Van Zyl, Iioni jewellery, Jewellery designer, South Africa.

Madri Van Zyl, Iioni jewellery, Jewellery designer, South Africa.

EK: The strong immigration in our country brings new ways of living the spaces, of consuming. Can these immigrants be a new target for a new design? What answers does design give to the new migration emergency?

As my friend from Zimbabwe once said “Africa is not poor, it just doesn’t have a lot of money”. What Africa has is the humanity. When I look at the immigration coming from Africa to Europe and the rest of the world, what they bring with them is that humanity. And the extension of that humanity is the sense of community. I have watched the ways that the technology has reduced the interaction between the people to a minimum. Technology in my view should be an enabler, but it should not replace human relationships. What I know about African communities is still very much “I am because we are”. So the way they bring freshness into European communities is by placing the human at the center of everything we do. Putting the human back into our business, social life, technological innovations, into our design. And it could be a very vibrant contribution.

EK: Today is the time to recover the social dimension of design and abandon or neglect that glamour that banalizes the design, but which is also often the only part that is being publicised. What do you think is the political role of the design?

I think that social design is the area that has to be invested in by all designers. You know, the legal profession inspires me, since they have this concept of pro-bono, where you make your money with the corporate sector, but you donate your money on a pro-bono basis for what they call “a good cause”. I would like to challenge the designers, even if it’s 20% of their time, to do socially responsible design. Today the world is going through an unprecedented chaos socially, economically, politically, we are more uncertain than we have ever been. At the same time we have more designers in the world than we ever had. Designers by nature are the optimistic people, professionally, if not personally. I call myself a critical optimist. Since we have a training in problem solving, the kind of world we live in today needs a design agency. As a designer you deliberately make a statement through the design choices you make, because each design choice has an impact on the society. But we don’t seem to be aware of that power. The last frontier of design is going to be in the political leadership. And I would challenge the designers to start infecting the political thinking and leadership of their countries with the kind of design skills and thinking that come natural to them. It could really help solve some of the problems, not alone of course, but together with other disciplines.

Can you comment on the educational aspect of design in Africa? Do you think there are enough design schools? Do you think they can be improved? Can you comment on the scenario?

Design education in Africa suffers from one thing: recognition. The recognition of the nature of design training. I was the first one in my family to go into design field and study it, and people didn’t really understand what the designers do (can you draw me?..) We are lacking the recognition from the government to acknowledge design as a full profession. In many African countries design is considered a semi-profession, unlike architecture, engineering or law. And the biggest challenge for me, having been a design educator, is to get the civil society members to recognize what design can actually do to contribute to their well-being. It means re-hashing our educational system to focus on the community engagement, so that we become co-designers with the community members and tap into their taciturn and embedded knowledge.

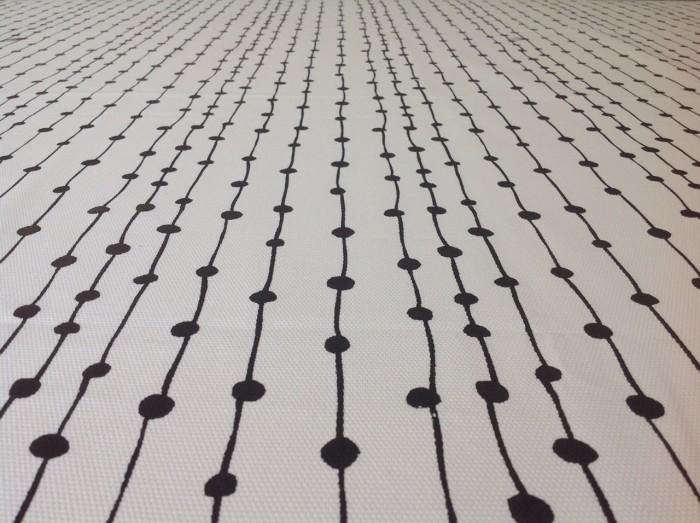

Megan Smith Billy button black, Textile designer, South Africa.

Megan Smith Billy button black, Textile designer, South Africa.

EK: The design looks at China for production and China looks at Italy for design. What lesson can Africa teach us?

What makes Africa unique is that the designs produced on the continent are driven by need. If I look at Italy as beacon of design thinking, creativity and ideation, Italy has some of the most famous brands globally. I don’t think any country can produce the amount of premium globally recognized designer goods per capita as Italy. And then you have China, which has literally become the factory for the rest of the world, manufacturing anything you can imagine. In Africa the manufacturing is happening at a much lower level. China is mass production, Africa is the production for need, so the hacker and the maker mentality is based on Africa. The second thing unique to the African context are the technological possibilities that have been introduced with 3D printing and rapid prototyping. My projection is that China’s hold on the world’s production is going to decrease with time. Because with the 3D printing and rapid prototyping there is going to be a new revolution, just as what desktop publishing did to the printing industry, where before only big publishing houses could publish and now anyone with the scanner and printer can do the same. The time is coming where we can democratize production. We have 3D houses, 3D food, 3Dvehicles. If Africa can live through a maker and hacking culture that we already have and that is part of our DNA, I think we can become self-sufficient around the year 2050.

Adama Sanneh: That’s in terms of production, what about in terms of consumption? Do you think we will be looking for the outside consumption and exporting the African design or do you think we will be also looking at establishing the consumer base within the continent?

I think it will be both. First of all, the 21st century by all economic projects will be Africa’s century. But it’s not going to happen by default, it has to be driven by design and creativity. If you look at countries like Nigeria, or Ghana or South Africa or Kenya you’ll see an expanding middle class that has been exposed to good design and creativity at a global level and they are demanding a better quality from their own people. The growing middle class in Africa is going to be a growing demand pool for African products. But for Africa to remain competitive it still has to export. Going back to the 80-20 split I think the bulk of what we produce will be consumed on the continent and the 20 % driven by excellence and quality will end up going out of the continent and will find a global market.

AS: On the one hand we are growing the middle class on the continent and there is a lot of potential, on the other hand often it still remains in this potential state. And from the branding standpoint the studies show that 80% of the brands that are perceived as quality brands are not African brands. So until we will not have African brands there will not be African agenda. So what has to happen so that there are a lot of African brands that are not only recognized outside of the continent, but also inside by the African economies, without running the risk of being diluted into a bigger anonymous African brand?

First of all governments must be much more proactive in the way they promote locally made solutions and products. We already find it in the TV content, where a lot of countries insisted that 90% has to be local content, which has become a catalyst for local creativity. The local element is the local elite. If they begin to be more “patriotic” towards the locally produced solutions, a lot can move in the future. For example, African music: you don’t need to sell African music to the Africans, they love their own music, same with African fashion. But when it comes to a different object, like a shoe or a hat or a car, then we start to get very fuzzy. If we can inject the enthusiasm of the African music and fashion into the African brand we can see it being sustained.

AS: How do you access the situation with the growing African elite in Nigeria and South Africa, etc. and how can they play a role of real drivers of the creative fields?

Siyanda Mazibuko Pate arts and crafts, Furniture designer, South Africa.

Siyanda Mazibuko Pate arts and crafts, Furniture designer, South Africa.

We have to step back and see the challenges faced by Africa in terms of unlocking that potential. I would say straight at the top is the politics. A lot of African elite do not have faith in their political system, so even if they are making their money locally, you will find it in foreign off shore bank accounts. So once they start trusting their political systems in the long term we will see a shift happening. Africa is one of the few places where you can still make profits, and you are right, the people are moving very fast into that elite bracket. But the wealth of Africa is spread too widely and too thinly, so if we could amalgamate the resources so that they have a critical impact we could be truly successful.

AS: What can organizations like yours do to educate and sensitize the consumers on the importance of local branding and production?

I think that Design Indaba and other design fairs in Africa are very helpful to showcase to the public what actually exists. Local people get pleasantly surprised about the quality of the local offer. So these organizations can bring industry and business into the same space. Usually the creatives lack a business acumen. When it comes to scaling up on the production of their beautiful objects they fall short. So our awareness creation could also be a sort of match making, bringing the entrepreneurial spirit into the creative space in a sustainable manner, then I think we will be on a trajectory of growth.

EK. The last question is what is the biggest stereotype you would like to subvert about the African continent?

The first one, and Binyavanga Wainaina spoke about it, is that Africa is not a country. It’s a big challenge for me. I travel around the world and people say “when you go back say hello to someone in Lagos” and I am in Cape Town, so… And another stereotype is that something that happens in one part of Africa somehow becomes an African issue. If there is a terrorist attack in one part of Africa then people say Africa is not safe. This idea of stereotyping Africa and lumping it up into a huge place is an issue. One of my most popular slides is called “The true size of Africa”, in which you see that China, the US, Europe disappear into it and there is still space to spare.

My disclaimer for this interview is that all these reflections are very personal, of an individual who spent most of his life on the African continent, but this is by no means to say that I understand the complexity of my own continent. As Kwame Nkrumah said: I am not an African because I was born in Africa. I am in African because Africa was born in me. And it can be born in anyone, you don’t have to have come from Africa. It’s an exclusive ethos. Africa can infect the world with its humanity again, with its joy and its richness.

With the support of