Speciale

Emotions, struggles, life, love, loss, between here and elsewhere

Why Africa? For many years lettera27 has been dedicated to exploring various issues and debates around the African continent and with this new editorial column we would like to open a dialogue with cultural protagonists who deal with Africa. This will be the place to express opinions, tell their stories, stimulate the critical debate and suggest ideas to subvert multiple stereotypes surrounding this immense continent. With this new column we would like to open new perspectives: geographical, cultural, sociological. We would like the column to be a stimulus to learn, re-think, be inspired and share knowledge.

Elena Korzhenevich,

lettera27

Here the column's introduction: Why Africa?

The exhibition The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Hell, Purgatory revisited by Contemporary African Artists has just closed at the SCAD Museum of Savannah. Inaugurated on October 16th 2014 it was the second chapter of the travelling project, which premiered earlier in the year at MMK Frankfurt and which is currently getting ready for a new appointment at one of the most important museums in the world. An exhibition that calls to reflect on universality, identity and belonging through the interpretation of Dante’s work by the most prominent African contemporary artists. The reinterpretation of the Divine Comedy becomes an occasion for a dialogue between African contemporary art scene and western cultural tradition. We can trace the particularities of each artist and different ways to approach the work as well as the common and essential traits that go beyond latitudes and time.

During the last months we have already opened a focus on the initiative on the pages of Doppiozero, starting from a conversation between the exhibition’s curator Simon Njami and art critic Elio Grazioli, followed by an essay by Roberto Casati. We are now back to explore it through a series of interviews by some of the exhibition’s artists, done by Contemporary And (C&), the online art magazine with the focus on contemporary art from African perspectives, during the premier at MMK in Frankfurt and generously offered to us for republication. We have selected some of the artists’ answers to build a journey through the subjective and multifaceted points of view of each artist that had to confront Dante’s masterpiece. It’s a collective tale of the project and its complexity, a project that mixes worlds and perceptions, moving through countries and cultures, the individual and the collective.

The Divine Comedy, exhibition view, ph. John McKinnon. Courtesy of SCAD Museum

C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s Divine Comedy. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work?

Zoulikha Bouabdellah: Although the Divine Comedy is an emblematic work of Western culture, it contains universal themes: questions surrounding punishment, death, and the body and its absence are obsessions shared around the world.

Aïda Muluneh: I don’t remember exactly when but it was a few years ago that Simon Njami mentioned to me that he was planning a show based on the Divine Comedy. Initially he told me to work on a collection based on paradise but eventually, I guess to provoke me in my creative process and knowing my personal life all too well, I was assigned with inferno. Coming from a place like Ethiopia, where religion is a way of life and a culture for us, it was interesting for me to see church paintings that depicted “hell”. Hence, since the exhibition is based on Dante’s body of work, it was relevant to understand his work in order to draw inspiration for how I perceived the inferno.

C&: In its merging of Christian beliefs and moral values as well as classical pagan topics, the Divine Comedy represents a deeply-rooted Eurocentric concept of society, values and culture. The exhibition aims at dismantling the European prerogative of interpretation and looking at it from a new angle. To what extent do you think this approach can lead to the Eurocentric interpretational sovereignty being generally put into question?

Aïda Muluneh: For me personally, it wasn’t necessarily looking at the Divine Comedy in the context of a Eurocentric concept, being raised within the Ethiopian Orthodox church, this wasn’t something extremely foreign to me. In all honesty, while creating the collection, I wasn’t necessarily thinking about Eurocentric ideologies. For me it was about trying to explore the notion of the inferno as it relates to my background and not necessarily politicizing or over-intellectualizing what I was producing, but rather trying to express things of the past and present.

Zoulikha Bouabdellah: There is an ever-growing intellectual movement, supported by thinkers and artists from places other than the West, that is advocating a decompartmentalized approach to the world. This exhibition is part of this movement. I subscribe wholeheartedly to this vision. It is so much more interesting to connect cultures with each other and to study their positive contributions.

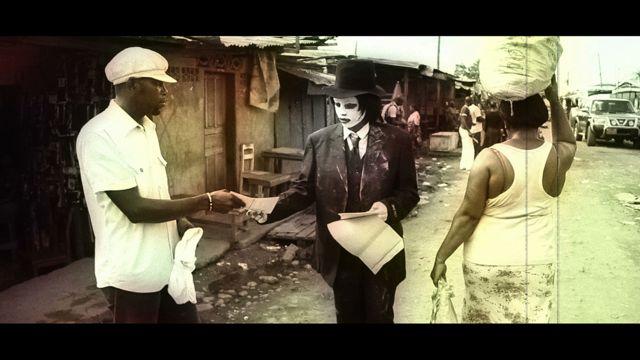

Ato Malinda, On fait ensemble, 2010

Ato Malinda: I’m not sure that I perceive the exhibition’s intentions as highlighting the hegemony of Europe. It is my understanding that Simon Njami wanted to align African art to the metaphor of Dante’s poem. That is not to say that the context in which the exhibition is being presented does not show awareness of Eurocentricity and the post-colony. In fact, this exhibition for me was about veering away from the obvious contexts African artists are continuously situated in, and to truly talk about (the experience of) art and poetry.

C&: In European-North-American art history, the Divine Comedy has been interpreted by numerous artists (such as Botticelli, Delacroix, Blake, Rodin, Dalí or Robert Rauschenberg) – what role did this play for you in respect to your engagement with the topic?

Guy Tillim: I have some ideas about my practice and find echoes in Dante’s poem through my experience with the camera that is informed by some self-reflection and contributes to a kind of revelation in this way: the scene in front of me speaks through me, or at least I should aspire to this state. The invisibility of self is desirable in what is mediated.

Guy Tillim, Near Huahine, 2011

Wangechi Mutu: What I find really poignant about the Divine Comedy, and why I actually use the Divine Comedy in this way, is its utilization of metaphor as a way of flushing out a particular issue. I love one of the things that Simon Njami said about Dante’s relationship with different people in Florence – that these stories he created for each and every person in the Divine Comedy were very personal, were based on his being ostracized in Florence, and that these massive narratives that he gave them really come out of this deep feeling of rejection. Then you truly understand that this guy was genius enough to create some place, like a god, for everybody to exist in. Especially for those he didn’t like, he created really difficult, torturous, eternal existences in that world. I think that’s very powerful and amazing. In my work, the creation of these enormous worlds and the placing of people within them, then the allowing of one's imagination to contort them, to punish them, to enrich them, to destroy them, is so important. That story becomes the salve, the medicine that allows you now to pursue a different way of life, a different thought. We can actually create spaces for the imagination to live out and play out all of these things. That is what I think is so important about the Divine Comedy and about art; it gives a space to play out these scenarios so they won’t happen in real life.

C&: How do religion and ethics feature in your artistic practice? And consequently, what do the terms heaven/hell/purgatory mean to you personally?

Kudzanai Chiurai: Religion and ethics are central subjects in my practice; I have often used them as an expression of time. The passing of time through lived experiences is one way of understanding religion and ethics, therefore the lived experiences will determine which realm you end up in and for how long you will be there.

Kudzanai Chiurai, Iyeza, 2012

Aïda Muluneh: In my photography, my main focus is obviously to document what I find interesting, and in my fine art photography, I find myself always drawn towards my personal experience of growing up like a nomad and seeing many different cultures. It’s not necessarily religion or ethics but more dealing with emotions, struggles, life, love, loss and so forth. Hence, when I think about heaven and hell, they are not something that is in another world but rather ever-present in this world, we don’t need to die to find them.

Guy Tillim: Ethics to my mind is not consequent on religion, those who would assume so or make it so create hell on earth. Heaven would be the absence of religion, finer points of ethics discussed in a Socratic way rather…

Zoulikha Bouabdellah: Religion as such doesn’t interest me; it’s what people do with it that makes me ponder. Silence (the piece participating in the exhibition) evokes the way in which women can find a place in sacred space—the prayer rug—while keeping one foot in profane space—the hole with the high heels. It is this complementary duality that recalls how heaven, hell, and purgatory are very close together and that it doesn’t take much—sometimes nothing at all—to shift you from one to the other.

C&: The over 50 art pieces in the exhibition are assigned to the areas heaven, hell and purgatory. What realm of the afterlife does your work belong in? How did this allocation come about?

Zoulikha Bouabdellah: Silence was chosen for inclusion in the heaven section. In Dante’s work, heaven is the culmination of a quest, the end of the soul’s voyage toward the light and eternal life. I like the analogy between heaven and the artist’s creative process, in which the latter brings warmth, gives light, instills meaning, and, as it were, delivers a piece of eternity.

Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Silence, 2008-2014

Guy Tillim: Paradise. When I met Simon at a soiree once in Paris, the first thing he said to me was, “Paradise or purgatory?” I said paradise.

Ato Malinda: My work belongs in purgatory. I feel that I sit well in purgatory. I never claim to have any definitive answers and I feel my life and my work is about finding space to accept the uncertainty of life. The work I submitted for this exhibition tells a story of African hybridity; an African identity that is influenced by Asia and Europe; an African identity that defies authenticity.

Kudzanai Chiurai: Purgatory is the realm my work is in. When I first started to conceptualize the video piece, I wanted to frame political conflict within religion and the best canonized reference was The Last Supper. I needed a point of departure from which I could construct a narrative that could express that. In the late 1990’s Nelson Mandela hosted a charity dinner attended by Charles Taylor, who was later prosecuted for human rights violations, and Naomi Campbell, who also testified at Charles Taylor’s trial. This was a perfect example of a space where saints and sinners gathered and of the conflict between ethics and religion.

Wangechi Mutu: In the exhibition, my work is situated in hell. But for me there is not a real separation between paradise, purgatory, and hell. I don’t really think in that way. I guess my work is not really so much in the afterlife as it is situated in the dream world, in imagination, nightmares as well as 'day-mares'. I’m a big believer in the interpretation of dreams. In African belief systems, we have another way of breaking it down: There’s the living, and the living dead, and the dead dead, and the unborn. The living are 'us' when are here, the living dead are the people who have died but retain a certain amount of power amongst us because they've just died. But mostly, the reason why they retain power is because the living dead are the people who are dead and who we still remember, the ones we pray to, or are still in touch with. They are living dead – they are still amongst the 'alive'. So the 'living dead' is probably my favorite. I think that my work lives in that realm if anything – not the after life, it’s the life, right after-life.

Wangechi Mutu, Metha, 2010

Artists and artworks

Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Silence, 2008-2014, Installation: 24 prayer rugs, 24 pair of shoes. Complete interview | Bio

Kudzanai Chiurai, Iyeza, 2012. Complete interview | Bio

Ato Malinda, On Fait Ensemble, 2010. Complete interview | Bio

Aïda Muluneh, The 99 Series', 2013. Complete interview | Bio

Wangechi Mutu, Metha, 2010. Complete interview | Bio

Guy Tillim, Second Nature, 2010-2011. Complete interview | Bio

Contemporary And

Contemporary And (C&) is an international online platform for diverse and critical insights into, and perspectives on, contemporary African art. The project is initiated and published by the German Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen – ifa (Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations). C& gives established and emerging artists, curators, art critics and other cultural producers from Africa and the diaspora the opportunity to reach an international audience and expand their networks.