Speciale

Zimbabwe’s spatial paradox

Ducking and weaving, side-stepping one, side-stepping two, brushing away shoulder charges and sprinting through to … the other side of the road, are my moves in the streets of downtown Harare and not the rugby field.

I consider myself to be spatially aware, I have a good sense of where objects are in relation to my body and can make the necessary adjustments when the aforementioned’s position changes. However, I can’t say the same for many Zimbabweans.

AtWork Harare, workshop at the National Hallery of Zimbabwe, ph Kresiah Mukwazhi.

The number of times I’ve stood in a queue and felt someones’ breath on my neck or their chest on my back are too numerous to mention. Normally a glare would make most back off, but instead, a vacant expression free of any guilt makes you look weird for not wanting a complete strangers’ body in your personal space.

Then there are kombis. The business is simple: get as many people to fit into the mini-bus as humanely possible. Nevermind the gear lever grinding on your thigh or the complaints of clients in a hurry, everyone knows space is money.

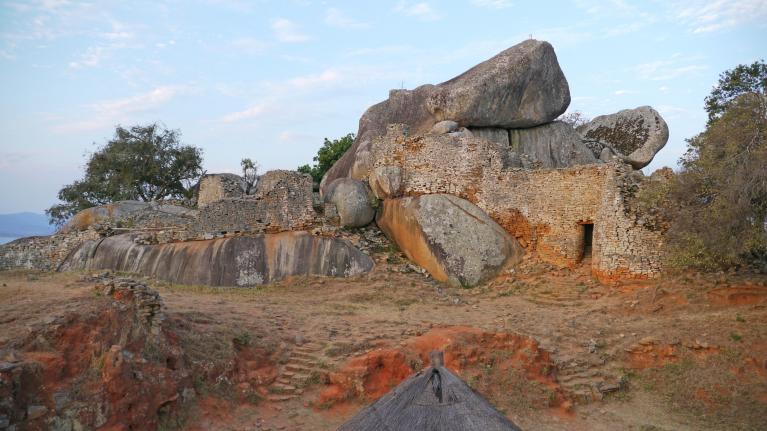

Great Zimbabwe, ph Simba Mafundikwa.

The vendors taking up a third of the street with their fruit carts on Robert Mugabe Rd are just another obstacle drivers need to avoid during the catastrophic 5 p.m. rush hour. This begs the question: Do Zimbabweans have a sense of space?

First it is important to put myself under scrutiny. I’m naturally introverted and have lived in low-density suburbs my whole life. Exploring gardens, riding bikes and retreating into my little house were all hallmarks of my childhood. You could say that space was never at a premium for me.

So it was a shock to the system when I visited Mbare, a southern high-density suburb created by the colonialists for the Black population, and in particular the communal housing buildings. Rooms the size of university dormitories are split into two by a curtain and forced to accommodate quite a few bodies.

Great Zimbabwe, ph Simba Mafundikwa.

The bathrooms aren’t that private either. While using the urinal, I had the feeling I was being watched and sure enough a man squatting down doing his business was staring at me. The lack of any barriers means that this type of situation is common.

People in Mbare may not live in the most spacious areas, but their close proximity to each other has created a sense of community that is rare in northern suburbs. As I was walking with a friend who lives in the New Lines neighborhood, he greeted and was greeted by all of his neighbours. We even cut through other peoples yards.

In Avondale, the suburb I call home, durawalls surround each property. Great for security and privacy but not conducive to familiarizing yourself with the people next door. You could always go and introduce yourself, but the spiked walls, ‘Beware of dog’ signs and electric fences might make you reconsider. This is at odds with the way pre-colonial Zimbabweans lived their lives . The areas were also low density but huts were built in close proximity, minus the walls, making it easy for people to share, talk and visit each other. Each individual was sharing space.

Harare city, ph Simba Mafundikwa.

What you see downtown today is a perversion of this idea of space. In a tough economic environment where cash is hard to come by. Many people have gone into vending and occupy the vacant rooms, pavements and streets of the city. While this introduces cheap organic produce and clothes, it is also unregulated and can be a pain when you’re trying to park for example. The spatial generosity has turned into spatial exploitation that is encompatible with the compact environment.

Amidst the chaos, there are still spaces for people with a project to exploit. My mother recently moved her dance school, AfriKera from a small rented space in a suburb to a vacant second floor of a department store. She now has a modern studio that can rival equivilants abroad in size. The intimacy, exclusivity, and central location of the space is also an advantage to dancers, instructors and visitors.

Then there are the spaces we occupied and visited during the AtWork workshop: The National Art Gallery of Zimbabwe and Njelele Art Station. At the former, it was interesting to have most of our meetings in an exhibition hall where people would come by, taking in the art on display. Our circle was set in a way that we could have our discussions without hindering or being hindered by visitors. Participants were able to open up, share and listen to intimate stories in this non-judgement zone. An openness that would’ve been under scrutiny in a normal familiar environment. Harmonious use of space.

Njelele Art Station is much smaller than the gallery but its diminutive size regularly welcomes the general public for thought provoking discussions and projects. To have a space likes this downtown where chaos reigns, makes Njelele a kindred spirit with AfriKera in the spatial repurposing of the city. During the workshop we were posed the question: Can revolution be a whisper? The aforementioned places answer: “Yes!” emphatically.

For the revolution to gather pace, it is important to have clear designated areas where vendors can operate and kombis dock. Basically the occidental method of separating spaces where locals can run their businesses without literally stepping on each other toes.

Harare city, ph Simba Mafundikwa.

I believe African and Western ideas of space can co-habit to form new spaces that everyone can benefit from. It just requires both sides to make concessions and as is common, the right financing mechanisms to be put in place.

Maybe the answer is in the past. The Great Zimbabwe ruins are the perfect example of harmonious use of space. Abandoned in the 15th century, every stone is measured and placed in a manner that works with the environment. The Hill Complex where the king lived, is constructed in such a way that the granite fortress looks like it’s fused with the hill.

After all of this, we go back to the question at hand: Do Zimbabweans have a sense of space? Yes but it is warped and mostly incompatible with the dated and unregulated, western infrastructures in town. Like other African countries, Zimbabwe’s journey to marry pre-colonial and colonial ideas of space is still at its genesis.